MURDER, HE WROTE

by Stephen Bowie

In 1963 Leonard Heideman killed his wife during a psychotic episode. Seven years later, using the name Laurence Heath, he was the producer of the hit TV series Mission: Impossible.

Leonard Heideman was having a bad year.

He had money trouble, for one thing. Heideman was a Hollywood screenwriter, with three feature films and dozens of television episodes to his credit. But nearly all of those were cheapies, pulpy B thrillers like Canyon Crossroads or Valerie, the latter an over-the-top vehicle for Anita Ekberg’s cleavage. Heideman spent most of his time in television, grinding out material for half-hour action programs like Highway Patrol, Men of Annapolis, and Panic! He wrote ten episodes of the infamous, commies-under-every-bed spy melodrama I Led Three Lives. These shows were produced for chump change by frugal indie outfits like Ziv or Meridian Productions. They always paid writers the minimum.

Three years earlier, in 1959, Heideman’s career had advanced to another level. David Dortort, the creator of Bonanza, hired Heideman to rewrite an early script for that series. Bonanza was a bland, meat-and-potatoes western, produced on a budget. But it was in color, and its comfortable tales of a rowdy, all-male frontier family struck a chord with audiences. Almost immediately, it became the highest-rated show on television. Dortort asked Heideman to join his staff as Bonanza’s story editor.

On Bonanza, Heideman took meetings with prospective writers and rewrote problematic scripts. Because Dortort liked to encourage new talent, Heideman was able to recruit an old friend, John Furia, Jr., to write a Bonanza script. Heideman and Furia had met in 1952, while serving together in the Air Force’s Burbank-based 1354th Video Production Squadron, which produced training films.

“He had an excellent story mind. He was really good at story structure,” said Furia. “That’s why I think he was so quickly successful, because he could come up with good stories for almost any series that was on.”

By the time Furia completed the order for three Bonanza scripts that his friend gave him, Heideman had left the western. Heideman had been putting in twelve- and fourteen-hour days on Bonanza, and he wanted more time to try his hand at serious writing. He also resented Dortort’s decision to add a second story editor to the show’s staff. A year before, he had been the story editor on producer Al Simon’s half-hour cheapies Flight (Air Force anthology) and 21 Beacon Street (private eyes). If he could handle those, why did Dortort think he needed help on Bonanza?

Walking away from a staff job on television’s number one show after less than a year could have been career suicide. But for Heideman, the gamble paid off – at first. He began to write for Checkmate, a big-budget detective series created by Eric Ambler. It was another step up. Heideman’s agent, Bob Eisenbach, a sometime writer himself, promised him that a big break was just around the corner. Some good notices could elevate him into the ranks of the top television writers, the talented echelon who crafted scripts for prestigious dramas like Naked City or Ben Casey. The ones who vied for the Emmy Awards every year.

In the meantime, though, Heideman was living beyond his means. When he began in the business, he had only himself to support. After the Air Force, he decided to hang around in Hollywood and try to break into the movies. It seemed like a sure thing. He had made training films in the service, and even before that – right out of Yale, before he turned twenty-two – he had gotten some film jobs from the New York-based producer Louis de Rochemont. Heideman had done coverage on Orwell’s Animal Farm for de Rochemont, and then rewrites on his films Whistle Stop at Eaton Falls and Walk East on Beacon.

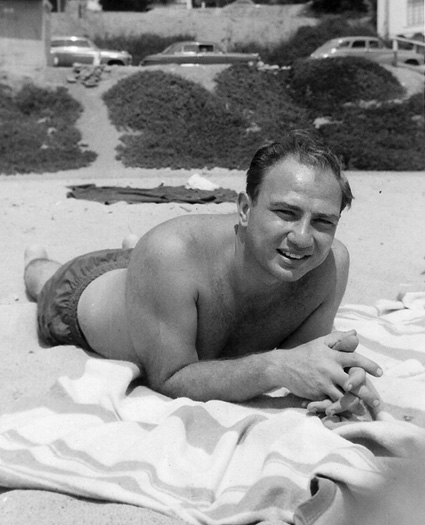

Heideman (behind desk) acts in an Air Force training film, circa 1952.

Discharged from the Air Force in sunny Los Angeles, Heideman partnered with another young writer who had worked on Beacon, a fellow Yalie named Emmett Murphy. Together they began to land a lot of television assignments. They split the modest fees between them, but it was still a comfortable living for a twenty-five year-old bachelor.

But Heideman had gotten married in 1955, to a woman he had known in New York, a schoolteacher named Dolores Hearn. Dolores was a pretty, vivacious woman, three years younger than her husband. Her friends called her Dorrit.

The Heidemans had two boys: Richard, born in 1957, and Kenneth, a year younger. They purchased a $50,000 hillside home in the West Valley community of Tarzana, far enough from the studios to feel like a suburb. Still, in the name, there was a reminder of how Heideman made his living. Tarzana had once been the ranch where another Edgar Rice Burroughs, creator of the literary ape man (and MGM movie staple) Tarzan, had lived and worked.

The Heidemans adapted quickly to the upper middle-class accoutrements available to a successful screenwriter. They employed a housekeeper, a woman named Esther Wilson, who made the long trek from her downtown Los Angeles home to clean theirs. Heideman bought the boys a dog, an expensive, curl-tailed African Basenji.

By 1958, Heideman was working without Murphy and keeping everything he earned, but there was a new drain on the family budget. Both he and Dolores had begun intensive, daily psychotherapy sessions, on which they spent over $20,000 in just a few years. When the Heidemans married, Dolores had given up teaching to become a full-time homemaker. But the therapy made finances so tight that Dolores went back to work, as a teacher at the Anza Elementary School in Torrance.

Money was not Leonard Heideman’s only worry. During the summer of 1962, his father, Charles, had died. Charles and his son had been close, and now Leonard had no intermediary in his tempestuous relationship with his domineering mother, Leah. Both his own parents and his wife’s had followed them to Los Angeles after Leonard and Dolores were married, and at times the Heidemans felt smothered by the omnipresence of their in-laws.

Then, in early February of 1963, the Basenji bit Heideman on the face. The animal control people had took it away to be quarantined in a shelter in Van Nuys, and the Heidemans awaited word on whether their pet might have to be destroyed.

Then there were the dreams. Lately Heideman had been experiencing bizarre nightmares in which he was a dwarf or a eunuch, suffering pain and torment. Nothing could prevent them. Only when Dolores ran a hot bath and eased her husband gently into the scalding water, talking soothingly into his ear – only then would he be able to get back into bed and enjoy something resembling a deep sleep.

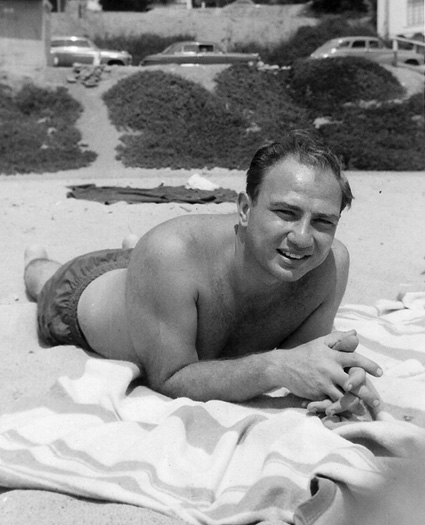

Heideman (second from right) with friends including writer Nicholas E. Baehr (in bowtie), circa 1958

*

The stress and the bad dreams and the lack of sleep were affecting Heideman’s work. Early in 1962 Heideman’s agent got him an interview on Sam Benedict, a new legal drama based on the exploits of the colorful San Francisco trial attorney Jake Ehrlich. MGM was spending money on this one. They had sent a crew to San Francisco to film the pilot, and hired a star, Edmond O’Brien, to play the title role. Lawyer shows were in: the best of them, The Defenders, had just won the Emmy for best drama. This was a chance at the critical success Heideman needed.

But Sam Benedict did not go well. Heideman met with the show’s creator, E. Jack Neuman, and the producer, William Froug, to pitch story ideas. He wore a suit and tie, and was embarrassed when he saw that Neuman and Froug were dressed casually. Heideman began to sweat profusely during the meeting. The other men noticed his discomfort, and sensed something was wrong. But they liked Heideman’s ideas, and gave him two assignments.

Heideman completed a rewrite of one Sam Benedict script, and the story outline for what would be his first original teleplay for the series. But he just couldn’t finish. With all of the other pressures mounting, Heideman found himself crippled by writer’s block. He missed deadlines. Finally Froug gave the script to another young writer, Ed Waters, to finish. When the finished segment aired on January 26, 1963, Waters’s name preceded Heideman’s in the credits. It was humiliating.

Three weeks later, on February 19, Heideman turned thirty-five. Middle age loomed on the horizon, and it seemed to him that he might never complete another script.

*

Heideman’s birthday was on a Monday. Four days later, in the early morning hours of Friday, February 23, Leonard Heideman killed his wife.

For most of the preceding Thursday, Heideman was busy making final preparations for a family outing. Friday was a holiday, Washington’s birthday, and the Heidemans planned to drive to Ensenada and spend the long weekend there. As the day wore on, Heideman’s nervous condition grew worse. He couldn’t stop worrying about the state of his career. Agitated, he telephoned his agent, again and again, the last time at 10 P.M. Eisenbach didn’t call him back. It confirmed what Heideman suspected: that Hollywood thought of him as yesterday’s news.

Heideman tried to sleep that night. The dreams made it impossible. Just before dawn, Dolores suggested the hot bath routine that had worked in the past. Heideman agreed, but wanted to be alone this time. Dolores insisted on helping him. As they argued, Heideman grew angry. He lashed out, striking his wife in the eye.

Suddenly Dolores was frightened. Something was different this time. Len had been violent before, but not like this. She ran out of the bathroom, out of the house. Her husband caught her at the front door. He pushed her back inside.

Heideman chased his wife through the house. They fought, violently enough to break furniture. As he ran through the kitchen, something caught Heideman’s eye. Something that gleamed. It was a long, double-handled pair of kitchen shears. Heideman picked them up. He noticed a lot of other sharp things in the kitchen. He picked them up, too.

Dolores was in the doorway between the kitchen and the dining room when he caught up with her. The shears went in first, or maybe it was the butcher knife. Blood flew everywhere. Finally Dolores fell to the floor.

“Len, stop it. I love you,” she pleaded.

Heideman, frenzied, continued his gruesome work, barely noticing where his jabs landed, slicing his own hands to ribbons. He struck at Dolores with a carving knife, until the long blade fell off. Then he grabbed a shorter steak knife, hitting his wife and the hard floor with it until the five-inch blade curled into a semi-circle. Then a kitchen chopper. Then the shears, which remained lodged deep in Dolores’ chest after her husband came to an exhausted stop.

Heideman’s weapons punctured his wife’s skin at least a dozen times; by his own later account, the total came to forty-nine. Seven of the blows penetrated Dolores’ heart. Heideman’s mind may have been fragile, but his aim was true.

The commotion awakened the Heidemans’ next door neighbors, Meyer and Eileen Berkowitz. They called the police. Dolores’s frightful screams also roused her oldest son, Ricky, who was then five. Ricky saw what was happening in the dining area and ran outside, to the Berkowitz home.

“My daddy is beating up my mommy,” Ricky yelled.

*

The police arrived at the house on 5060 Shirley Avenue just after 6 A.M. The uniformed officers, Glen Kailey and William F. Powers, went in first. They found the bloodbath in the kitchen, and started a search of the rest of the house. In his bedroom, they discovered the Heidemans’ youngest son, Kenneth. The press reported that he had slept through the carnage.

Heideman ventured toward them from a room in the rear of the house. He was naked and soaked in blood. He asked Officer Powers if Dolores was dead. “It’s all a mistake,” he said, according to the newspapers.

“She had my balls. I had to get my prick back,” were Heideman’s actual words, by his own later account.

Then Heideman babbled something about having taken pills. The officers rushed him to Northridge Hospital, where his stomach was pumped. At some point, either before or after killing his wife, Heideman had attempted suicide. From the hospital, Heideman was moved to the West Valley Police Station.

At 9 A.M., Bob Eisenbach arrived at his office and found Heideman’s message from the previous night. He returned the call. The police answered the phone.

*

“I lost my head,” Heideman told his interrogators. “I went out of my mind. If only I could turn back the clock.

“We have to go on a trip today,” Heideman said, referring to the Ensenada vacation that would never happen.

Detective Sergeant O. D. de Ryk and his partners, Lynn Selby and Don Zellers, questioned Heideman throughout the weekend. De Ryk checked into the writer’s medical history and learned some disturbing details. Heideman had been violent toward Dolores before, had tried to strangle her. He had checked himself into a rest home for a week following that incident, and had since remained under a psychiatrist’s care.

“I’ve written this scene before,” Heideman said, dazed, as he looked around at the police station walls, so similar to the police stations he’d written into his TV scripts. Dolores’ death was all too real, but for a movie writer, it felt like a scene from the screen.

The Heideman wedding in 1955: Dolores and Leonard at left; the groom’s parents Leah and Charles Heideman at right.

*

Things moved quickly over the weekend. The Los Angeles Times and the local TV stations ran lurid accounts of the crime. The Associated Press picked up the story and disseminated the gory details of Dolores’s death in papers all over the country. Dolores was autopsied on Saturday and buried on the morning of Sunday, February 25. Her husband remained in his cell as Rabbi Julian Feingold conducted the funeral service at the Hillside Memorial Park Chapel.

Ricky and Ken Heideman stayed with Mrs. Wilson, the maid, for about a week, then moved in with Dolores’ parents, Samuel and Helen Hearn, who lived in West Hollywood. The Heideman children were, for all intents and purposes, orphans, and the Hearns decided to adopt them.

In August, the house at 5060 Shirley Avenue went on the market. “Immediate sale – urgent,” read the classified ads. By the time the listing disappeared from the Los Angeles Times, the price was down to $45,000: five grand less than the Heidemans had paid for it years earlier.

5060 Shirley Avenue, Tarzana, California, present day. The former Heideman house appears largely unchanged since 1963; the ivy bed and terraced walkway are visible in crime scene photos.

*

On Monday, February 26, Heideman was arraigned in the Van Nuys Municipal Court. Judge Francis A. Cochran ordered him held without bail. Heideman spent the next five months in a prison cell.

At various points during his defense Heideman was represented by three attorneys, all past or future celebrities in the Los Angeles criminal justice system: Godfrey Isaac (“Hollywood’s Hottest Trial Lawyer,” per the dust jacket of his 1979 memoir), who successfully represented celebrity coroner Thomas Noguchi after he was controversially fired by Los Angeles County; Maxwell Keith, who later defended Manson follower Leslie Van Houten; and Grant Cooper, who would be Sirhan Sirhan’s trial attorney. Isaac and his wife had been friends and neighbors of the Heidemans before they moved into the Tarzana home, and because of his emotional involvement in the case he brought Cooper, already a high-powered trial lawyer, to defend Heideman in court.

Cooper’s fee was sizeable. Heideman’s remaining friends in the industry contributed money to pay for his defense. The leader of the fundraising effort was the actor Wesley Lau, a close friend from Heideman’s Yale Drama School days who was then playing a regular role as a police detective on Perry Mason.

On May 22, Heideman appeared before Superior Court Judge John G. Barnes and offered pleas of not guilty and not guilty by reason of insanity. During the next seven weeks three psychiatrists examined Heideman, and all agreed that the writer was legally insane. (At least one of them offered the medical diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia.) On July 15, Judge Barnes declared the writer unfit to stand trial for the murder of his wife. He ordered that Heideman be committed for an indefinite period to the Atascadero State Hospital.

Atascadero was an all-male, maximum security facility for the criminally insane. Heideman spent fourteen months there. On a day in the late summer of 1964, the writer returned to the same courtroom, where the judge accepted both his plea of not guilty by reason of insanity and the Atascadero staff’s testimony that he had fully recovered. Leonard Heideman was a free man.

Perry Mason so-star Wesley Lau, far left, with Leonard Heideman (second from left) and other unidentified friends

*

On October 29, 1966, a segment of Mission: Impossible entitled “Wheels” was broadcast for the first time. Mission was a clever, action-driven, austere spy show that would become a long-running hit. “Wheels,” a story of voting fraud in a Latin American country with a rather flimsy twist ending, marked the television debut of a writer named Laurence Heath.

Laurence Heath, of course, was the new name that Leonard Heideman had adopted following his release. Originally Heath was a pseudonym, but he soon changed it legally. “Heath” was a literal translation of the German word “heide.” Over the years, some of Heath’s colleagues would assume that his new name was a reference to Bronte (Laurence Olivier had portrayed Heathcliff in the 1939 film of Wuthering Heights). This was apparently not the case. But Heath’s decision to keep the same initials was a writerly touch, rooted less in pragmatism than in a pulp craftsman’s axiom that a criminal on the lam always made sure his alias matched the monogram on his valise.

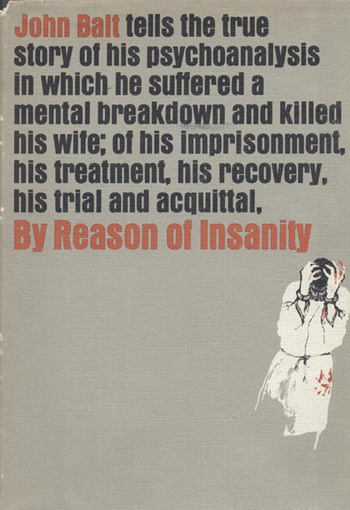

Heath’s third script for Mission: Impossible, entitled “Shock,” tackled a subject that the author knew intimately. In “Shock” the Impossible Missions Force abducts an enemy spy, Carl Wilson (played by James Daly), and imprisons him in a phony mental hospital. In order to trick Wilson into revealing his secrets, the team convinces him that he has suffered a breakdown and forgotten his true identity.

Wilson finds himself locked in a tiny padded cell, bound inside a straitjacket. He is subjected to painful electroshock treatments, with a rubber wedge jammed between his teeth to keep him from biting off his tongue. The electroshock therapy causes frightening hallucinations, and Wilson breaks after the IMF agents inform Wilson that the voltage may lead to brain damage.

“It’s easy to forget that the victim is in fact a villain and his stone-faced torturers are heroes,” wrote Mission: Impossible historian Patrick J. White, who called the episode “disturbing” and “sadistic.”

James Daly in “Shock”

*

One might jump to the conclusion that “Shock” was autobiographical. But if Heath’s account is to be believed, his own hospitalization was quite different from Carl Wilson’s.

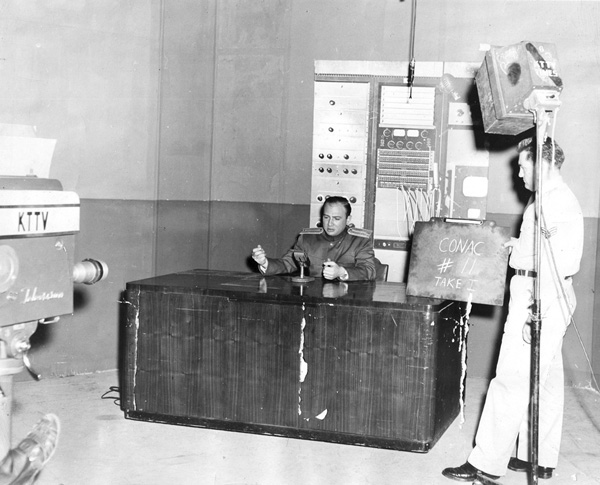

Heath spent the year following his release writing an account of his crime, trial, and treatment. It was published in 1966, with the title By Reason of Insanity and under yet another nom de plume, John Balt. The book revealed a basic fact that had eluded the press in their coverage of Dolores Heideman’s death, and also many of Heideman’s friends and relatives prior to the event: that the writer had been suffering from a deep and dangerous mental illness for more than a year before he killed his wife.

Dolores, aware that the perception of frailty could doom a Hollywood career, had kept her husband’s condition hidden from the world, even after perceiving a danger to herself. The boys, young as they were, felt that something was wrong, too. “Daddy, would you ever hurt mommy?” Ken had asked his father during Thanksgiving dinner in 1962. On his thirty-fifth birthday, Heideman had threatened suicide, growing so agitated that Dolores came close to calling the police.

Heideman had sought treatment from three different doctors (two psychiatrists and the family internist), but in his estimation, the daily psychoanalysis and the drugs they prescribed did not heal him. Instead they triggered his psychotic break. This view was the basis of Heideman’s legal defense, and also the moral position to which he clung in By Reason of Insanity.

In the book, Heath credits a compassionate female doctor, a refugee from the 1956 communist takeover of Hungary, with his recovery. Though he mentions in passing that his earlier doctors were Freudian in their approach and that the Hungarian woman (whom he calls “Dr. Keszi”) was a Jungian, Heath depicts them less as trained professionals than as black and white knights. He offers little insight as to why millions of other people who received similar treatment did not also commit lethal mayhem. Heath’s conclusions about the cause of his moment of homicidal rage come across as pat and self-serving.

In spite of that, By Reason of Insanity – specific, urgent, and unrelentingly grim – is likely the best writing that Laurence Heath ever did. Its strongest passages describe in almost unbearable detail the pathetic state in which the writer existed during the first months of his incarceration. Consumed by paranoia, Heath convinced himself that his jailers, his doctors, and even his attorneys were conspiring to send him to the gas chamber. He heard voices in his head and hallucinated that President Kennedy visited him in his cell. He masturbated compulsively. And he attempted suicide over and over again, rigging Rube Goldberg devices that all failed: putting a finger in a light socket and a toe in a sink filled with water; trying to guillotine himself with the metal edge of his bunk; eating cigarettes to poison himself with nicotine.

Unlike the doctor-torturers in “Shock,” the medical personnel and even the penal employees in By Reason of Insanity are professional and sometimes even kind. Was Heath using metaphor in “Shock,” externalizing his own internal torment but retaining its emotional truth? Or was he already able to compartmentalize his own trauma and write impersonal fictions that covered the same ground? During the year of unproductive analysis that led up to his breakdown, Heideman found his scripts being rejected as “too psychological.” Laurence Heath would not make that mistake again. From now on, he would not probe the dark corners of his own mind for inspiration. He would write for the market.

*

Heath had a strange connection to Mission: Impossible that dated all the way back to the late fifties. Just prior to Bonanza, Leonard Heideman had written the pilot for and then story edited a spy show called 21 Beacon Street. Beacon went off the air after thirteen episodes, only to resurface in a plagiarism suit between Filmways (which had produced Beacon) and Bruce Geller. Filmways alleged that Mission: Impossible’s trademark apartment scenes and its emphasis on gadgetry, among other elements, were lifted from 21 Beacon Street. Geller told Heath that he’d never seen Beacon – but he paid Filmways off anyway.

Heath began work on Mission before the 1968 lawsuit was filed, and his hiring may have had nothing to do with his role on the earlier show. But no one, including Heath himself, could have been surprised that he would pen some of the most popular Mission: Impossible episodes, including “The Mercenaries,” about a masterful gold heist; “Illusion,” in which Cinnamon Carter (Barbara Bain) impersonates a cabaret singer; and “The Exchange,” another dark tale of torture and claustrophobia, with Cinnamon the victim this time. Heath was one of a handful of writers who could master Mission: Impossible’s unique format of complex puzzle-box caper stories. Along with only Paul Playdon and the team of Allan Balter and William Read Woodfield, Heath delivered the series’ most intricately plotted scripts. (“Shock,” for instance, is a story of multiple impersonations, in which James Daly plays a triple role.)

“He wasn’t big with imagination. He was big with the logic of the story, and the characters,” said Bruce Lansbury, producer of Mission’s last three seasons.

“In a world that was quite undependable, Larry was a very dependable man. If he took an assignment, you got the results in a very orderly way,” said Stanley Kallis, who preceded Lansbury as the producer of Mission: Impossible. “He was a good writer, and I think that his shows were always at the top of whatever series that he worked for.”

Heath was lucky. Mission: Impossible was a big hit, and it allowed him to start over again right at the top. Freelance assignments on other top action and mystery shows poured in. The most enduring of these was The Invaders, Quinn Martin’s spooky venture into science fiction paranoia, for which Heath wrote four segments. The best of those was an optimistic, premise-changing script (“The Life Seekers”) which posited that a non-violent resistance movement existed among the emotionless extraterrestrials who sought to colonize the earth.

Producers noticed that Heath could deliver shootable teleplays quickly, and he was able to network his way into a lot of work. Another Mission: Impossible producer, Joseph Gantman, recruited him for an early Hawaii Five-O episode. Mannix, a Bruce Geller creation like Mission, purchased one Heath script. Alan Armer, the producer of The Invaders, brought him in to write for his next project, the western Lancer.

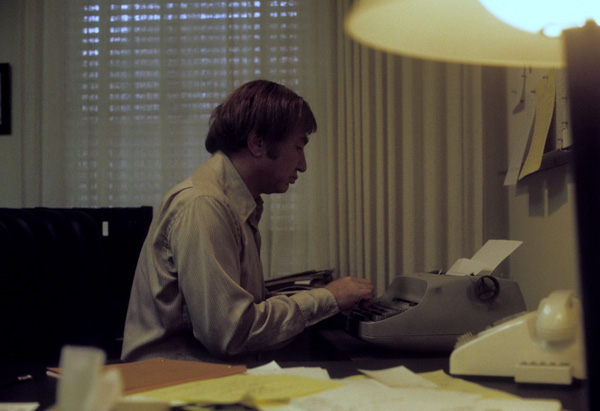

Laurence Heath, writing for Mission: Impossible, in 1972

But Mission was the show that cemented Heath’s reputation as a plotting wizard, and it was there that he would become a story editor again and a producer for the first time. By the fifth season, many of the most talented people had left – Geller, Balter & Woodfield, cast members Martin Landau and Barbara Bain – and Mission was widely perceived to have run out of ideas. Paramount placed Bruce Lansbury, the younger brother of the actress Angela Lansbury and recently the producer of The Wild Wild West, in charge. Lansbury inherited Heath, by now the most experienced Mission writer who was still around, and made him the show’s story editor. The pair would be responsible for most of Mission’s content for its final three years (from 1970 to 1973), and Heath received a producer credit on some episodes.

As writer Stephen Kandel explained to Patrick J. White, “Larry Heath defined the show because he was in charge of the scripts.” In today’s terms, he would be considered Mission’s showrunner.

“Heath and Lansbury were marvelous to work for,” writer Norman Katkov told White. “Heath was very helpful, wanted you to have the story, wanted to give you the job.”

Lansbury and Heath never defeated the perception that Mission: Impossible was creatively spent. They tried the usual stunts, like introducing younger cast members (Sam Elliott, Lesley Anne Warren) and moving away from the stoic caper format to tackle more personal, character driven stories. A key Heath script was “Homecoming,” in which Peter Graves’s character, Jim Phelps, returns to his home town to solve a crime involving his old girlfriend. Flashbacks help to illustrate the backstory of a hero who, in Geller’s original conception, would remain a cipher. Nearly every crime show of the sixties and seventies did an episode like “Homecoming” – and that was the problem. Many of the show’s fans felt that the changes introduced by Heath and Lansbury diminished the qualities that made the series special.

Heath’s friendship with Bruce Lansbury was to be the most important professional relationship of his new career, one that would extend all the way to his final job in Hollywood. After Mission: Impossible was cancelled, Lansbury and Heath went on to oversee another Paramount production, a series called The Magician, which reunited much of Mission’s creative team and sought deliberately to imitate its tricky storytelling formula. Bill Bixby played a magician and escape artist who also solved crimes. This time, Heath was the executive producer.

The Magician has a small cult following today, but its production was beset by clashes between Bixby and the producers, cast and crew changes, and a crippling Writers Guild strike. The show was cancelled after a single season. Heath, though he retained his on-screen credit, was tossed out after twelve episodes.

But Heath had written The Magician’s pilot, and that credit paved the way for Heath to move into the world of series pilots and made-for-television movies, which were at the apex of their popularity in the mid-seventies.

Heath wrote the pilots for the short-lived Most Wanted, starring Robert Stack (the Los Angeles Times called his script “tired out”), and the firefighting drama Code Red. He produced Khan, a 1975 crime drama about a Chinatown P.I. (played by Khigh Dhiegh, Hawaii Five-O’s Wo Fat) that lasted for only four episodes. He wrote movies of the week – Ski Lift to Death, The Beasts Are in the Streets – which borrowed from the disaster films that were popular in cinemas at the time. Heath found a new specialty in melodrama, penning soapy mini-series (Seventh Avenue, Sins) and adapting schlocky best-sellers (Valley of the Dolls, Dazzle) into TV movies. He spent a season as a staff writer on Dynasty in the late eighties.

It was a journeyman’s career, one that brought Heath lucrative work but little critical cachet.

When Henry Kissinger visited the Mission: Impossible set in August 1971, it was Laurence Heath who showed him around the Paramount lot

*

How does a man kill his wife, avoid criminal punishment, and go on to become the primary creative force behind some of the most popular entertainment on television? In some fields, Laurence Heath’s backstory would make a person unemployable. In Hollywood, it was just another good story.

“It’s a business where if you can’t put up with a mild amount of eccentricity, you should leave,” said Stephen Kandel, who wrote for Heath on Mission: Impossible and was his story editor on The Magician. “Bizarre comes with the territory.”

Heath later claimed that about half of his friends had abandoned him after Dolores’ death, and the other half stood by him. (John Furia, Jr., was one of the people who never re-established his relationship with Heath following his release.) One ally was a devoted agent, who would call producers and patiently explain Heath’s delicate personal history, reassuring them that the writer was now totally functional. Another was Wesley Lau, and Heath would repay the favor by hiring Lau as both an actor and a writer on Mission: Impossible.

Much of Leonard Heideman’s past became part of Laurence Heath’s official resume: his childhood in the Bronx (where one schoolmate had been another future television writer, Lila Garrett, an Emmy nominee for Get Smart and My World and Welcome to It), his undergraduate degree at New York University and MFA at the Yale Drama School, his rank of lieutenant in the Air Force. But he could be cagy about his past when it came to publicity. A 1975 newspaper article gave his father’s name, inaccurately, as Charles Heath.

“He would talk about it if someone asked,” Bruce Lansbury said of the defining event in Heath’s past. Not that there was much to say: Heath always claimed that he remembered nothing of the crime itself, only of awakening afterward, nude, on his front lawn. Heath spoke more freely of his treatment and recovery.

“He was quite open about the event,” Lansbury went on. “He had to be. Everybody in the business knew who he was, and he worked with a lot of people.” Heath took to loaning copies of By Reason of Insanity to his closest collaborators when he joined a new series. It was a way of telling his version of the story without enduring an endless series of awkward conversations.

*

Taken together, the memories of Laurence Heath’s co-workers create a portrait of a soft-spoken, likeable loner. They also paint Heath as a man with some unusual quirks and a voluble temper.

“He was perfectly nice, and I got along fine with him,” said Walter Grauman, who directed several of Heath’s scripts. “But he was a little strange. Quiet. Somewhat introspective.”

Stanley Kallis described Heath as “very withdrawn,” although he noted that Heath sometimes clashed with Paul Playdon, a Mission: Impossible story editor, over rewrites. A relative of one of Heath’s colleagues observed that Heath was very competitive even in conversation, that he seemed compelled to engage in a sort of intellectual one-upmanship.

“I got along with him reasonably well,” said Stephen Kandel. “But I once had a really explosive argument with him about something. He had a kind of a hair-trigger temper. But it was funny, because it was on and off. It would be unexpected things that would trigger it.

“I mean, you’d have an argument. ‘This is terrible.’ ‘No, it’s not. Let’s talk about this.’ This is reasonable. But then, ‘Do you have to include that potato salad?’ ‘POTATO SALAD?! GODDAMN IT, DON’T TALK TO ME ABOUT POTATO SALAD!’ You know, completely irrational.”

At one point Kandel could not resist making a joke about Heath’s rather obvious hairpiece. “He got furious at me and I said, ‘Don’t flip your wig, and I mean that literally,’” Kandel recalled. “He got all red. I said, ‘Listen, I’m sorry, Larry, but it’s just the worst rug I’ve ever seen.’”

Laurence Heath in 1972

*

It is possible that Heath hired a publicist to help relaunch his career. At least, that’s the only sensible explanation for the bizarre item that appeared in reporter Matt Weinstock’s Los Angeles Times column on December 11, 1968.

“For a long time,” Weinstock wrote, “writer Laurence Heath has been awakened at 5 a.m. on Sundays by the loud and continued barking of a Great Dane in the neighborhood.” Once again, Heath’s tormentor was a canine. For anyone who knew the details of the Heideman killing, the blurb must have read like a tasteless in-joke. Heath, the story explained, deduced that the loud thud of the morning paper was what bestirred the dog, and countered by rushing outside to retrieve the paper. This silenced the animal and, “not only that, he gets a three-hour jump on the rest of the household in reading the paper undisturbed.”

By 1968, “the rest of the household” comprised a new wife and baby. Heath had met Carolyn Zimmer on the ski slopes in Mammoth, California. Zimmer was a tournament skier and a former English major at Spokane’s Gonzaga University, where her roommate had been a young actress named Sharon Gless.

Laurence and Carolyn Heath, circa 1968.

When Heath married Carolyn on December 2, 1967, he was still legally Leonard Heideman – and his new bride was seven weeks pregnant. Heath was 39; Carolyn was 24. After their son, Charles, was born in June 1968, Carolyn gave up her job as a children’s hospital administrator to become a full-time homemaker. The couple asked Sharon Gless to be Charles’s godmother. A daughter, Elizabeth, followed four years later.

[Author's note: "Elizabeth Heath" is a pseudonym. Upon its original publication, this article used "Elizabeth"'s true name. At her request, it was changed retroactively in March 2014. No other names have been changed.]

The new family lived in a Brentwood home that Heath had purchased with his Mission: Impossible money. Ironically, their residence at 151 Tigertail Road had, like the Heideman house in the Valley, been a site of tabloid-worthy domestic strife. It was the home in which Marlon Brando had lived with Anna Kashfi in the late fifties, and where Kashfi attempted suicide after her split with the actor.

Like the Brandos’ union, Heath’s second marriage did not last. Leanna Johnson was a Long Beach-born dancing instructor, model, beauty pageant winner, circus contortionist, and aspiring actress who met Heath during an audition for a bit part on Mission: Impossible. Sometime shortly before or after his divorce from Carolyn in 1974, Heath began an affair with Leanna. They were married in August 1975. Heath was 47; Leanna was 24.

|

|

Leanna Johnson Heath’s acting career never took off, although she did rack up small parts in Blacula, Bound For Glory, and some television shows, including the pilot for her husband’s series Khan. At Heath’s urging, Leanna studied law and eventually worked as an entertainment attorney for several film studios. She bore Heath’s fifth and final child, a son named John, in 1978.

Carolyn had not asked for custody of her children, who grew up, along with John, under their father’s and Leanna’s care at 151 Tigertail. Heath was not warm or demonstrative by nature, but “he was responsible and he was there,” according to his daughter. Most days he remained in his office, writing from nine in the morning until six or seven at night. Heath’s main gifts to his children were his intellectual passion and his dogmatic work ethic.

“I would hang out with him a lot in his office, and he had a little chair for me. A little place for me to work,” said Elizabeth. “I always felt almost like a creative equal with him. Even as a little kid, he would talk to me about story ideas and bounce ideas off me.”

But the Heath household was built on secrets, and eventually it crumbled. Heath chose to tell his children nothing of his past as Leonard Heideman: nothing about the death of his first wife, nothing about their half-siblings in Massachusetts. That decision meant keeping his personal life isolated from his professional life, so that Heath’s industry friends would not say something careless around the children. Once, when Elizabeth found the Heidemans’ wedding album in the garage, her father snatched the book out of her hand and told her not to go into that room again. One day, Heath figured, he would tell the children everything. As soon as they were old enough to understand.

But that day never came. In 1991, the stresses in Heath’s life overlapped just as they had in 1962. He hadn’t worked in two years, and was struggling to keep up with the mortgage on the Tigertail Road house. His marriage to Leanna was falling apart. Heath had a second breakdown, and again he was hospitalized.

“It was a horrific year. I really saw him sort of descend into total insanity,” said Elizabeth. “After that he was always kind of mentally fragile.”

Only then did Elizabeth, who was nineteen, finally learn the truth about Dolores Heideman – and not from her father, but from her stepmother, who feared that Heath would turn violent again. Elizabeth found her father’s book. “I read it once, threw it in the closet, and went into therapy,” she said.

*

Heath had dedicated By Reason of Insanity to young Ken and Rick Heideman. “To my two young sons,” he wrote, “who are still too young to understand; but who, I hope one day . . . will be able to return my love.” That would take more than thirty years.

In 1964, upon learning that the boys’ father would soon be released, Sam and Helen Hearn decided to move their new wards from Los Angeles to Newton, Massachusetts, where they would be far from Heath and close to their extended family. It was a sacrifice; the colder climate made Helen’s osteoarthritis worse. The Hearns, then in their mid-fifties, created a warm, lower-middle class home for Ken and Rick. Leonard Heideman was his father, Ken would later say, but Sam Hearn was his dad. The Hearns received child support from Heath (“a pittance, some ridiculous amount like $100 a month,” according to Ken Heideman), but the writer had no direct contact with the boys.

The tragedy of 1963 loomed over the Hearn household. Helen often cried when she thought of her daughter. Sam was ambivalent toward his former son-in-law. He had been close to Leonard Heideman, had believed in his moral innocence and assisted in his legal defense. Now he watched the TV shows that Laurence Heath wrote with a strange sort of pride. Helen, appalled, would leave the room.

With the boys, the Hearns adopted a strategy of denial on the subject of their mother’s death. Ken and Rick were instructed to tell their schoolmates that both their parents had died in a car crash. The Hearns hid their copy of By Reason of Insanity in a desk drawer that they warned the boys never to open. Ken, eight years old when the book was published, was seventeen before he sneaked it out of its cache and read it furtively. Rick Heideman still has not read his father’s book.

For Ken Heideman, the secrecy had unfortunate consequences. During his sophomore year in college he suffered a crippling bout of depression. He pulled himself out of it, but soon suffered a relapse; only then was he diagnosed and treated. Heideman forged a successful career as a meteorologist, writer, and public speaker, but organized his life around the periods of severe depression that continued to plague him. Only after two decades of therapy did he begin to feel free of mental illness.

One of Heideman’s ways of coping was to confront the tragedy head-on, to bring up the subject with family members who would have preferred to leave it buried. In therapy, he remembered long-buried details about the night of his mother’s death. He realized that he had not slept through the fatal assault, as the papers had reported in 1963. Instead he had pretended to sleep, hearing his mother’s screams through the bedroom door, too afraid to run to her aid as his older brother had done.

Finally, in 1992, Heideman reached out to the father whom he hadn’t seen in thirty years. Heath agreed to travel to the east coast to meet Ken and Rick (who, after wavering until the last minute, opted to go along) on their own turf. Later Ken went to Los Angeles to meet his half-siblings, and Heath began to make regular trips to Boston to see his eldest sons and their families.

Ken never confronted his father directly about his violent legacy. But Heath took a liking to Ken’s then-wife, a social worker, who would ask more probing questions – questions along the lines of, how could Heath live with what he had done?

“He’d answer: ‘Well, it’s difficult, so I try not to be alone very much,’” Ken recalled. “He wasn’t denying that he’d done this, and he wasn’t denying that it was a horrible thing.” On one level, Ken empathized with his father; on another, he resented the older man’s disengagement, his decision to hand the boys off to their grandparents and absent himself from their upbringing. It wasn’t until 2004 that Ken realized that he had forgiven Heath, and told him so.

“I think he was moved by it,” Ken said of his father’s reaction. “But he was not a real engaging type of individual. He wasn’t a warm guy.”

*

It is hard to imagine a more ironic credit for Heath than Murder, She Wrote, with its Agatha Christie-inspired conception of homicide as an anodyne parlor game. But after his second breakdown, Heath desperately needed a job. His old friend, Bruce Lansbury, came through, hiring Heath as a freelancer on Murder, which Lansbury was producing for his sister Angela, the show’s star. It may have been an act of charity, but Heath’s aptitude for complicated plotting was a good match for Murder, She Wrote. In all he wrote ten scripts for the series, and after a year Murder’s showrunner, Tom Sawyer, brought Heath onto the staff as a producer.

Murder, She Wrote was to be Heath’s final professional credit, and ultimately it was not a happy experience. Sawyer grew annoyed with Heath’s argumentative nature and decided to fire him. He was overruled by Bruce Lansbury, and Sawyer retaliated by refusing to deal with Heath at all and insisting that Lansbury handle any necessary rewriting on Heath’s scripts. Heath stayed with the show until it went off the air in 1996, but Sawyer hired another story editor to take over many of his responsibilities.

Throughout Heath’s four-year association with Murder, She Wrote, Sawyer and Bruce Lansbury conspired successfully to keep the facts of Heath’s history from the show’s star. The pair felt that, had Angela Lansbury known about Heath’s past, she would have fired him for fear that the story of Dolores’ death might resurface and envelop the show in a scandal.

*

After his third marriage failed, Heath had become a somewhat compulsive, if unlikely, serial dater. “There always had to be a woman in his life,” according to his daughter.

Heath’s last girlfriend was an American Film Institute staffer named Joan Barton. Joan had been married for three decades to another talented television writer, Franklin Barton. Heath had worked with Franklin Barton on a 1977 miniseries called Seventh Avenue, but he did not meet Joan until 2004.

After their first date, Joan Barton mentioned Heath’s name to a friend who related the story of Dolores Heideman’s death. Barton was startled, but she liked Heath’s intelligence and wit, and decided she would give him two more chances to tell her about his past. Heath offered his explanation of the 1963 killing on their third date, and the couple continued to spend time together.

Heath was in his seventies now, but remained physically active. He skied and played tennis regularly. A jogger, he ran up and down the Santa Monica stairs twice a week. It was tough for Heath to get work, but he read a great deal and worked energetically on several spec scripts.

Late in 2006, Heath had lunch with Bruce Lansbury for the last time. They discussed old times, and old age. Heath was having trouble with his hearing, and Lansbury encouraged him to get a hearing aid. “No, my fingers are too fat” to operate the device, was Heath’s reply.

Lansbury noticed nothing amiss, but Heath’s children and Joan Barton were beginning to observe symptoms consistent with Alzheimer’s disease – and also alarmingly reminiscent of his 1991 breakdown. One night, after meeting at a restaurant for dinner, Barton and Heath walked back to their cars together. Heath’s car was parked on Wilshire Boulevard, with the headlights on. He had left the motor running the whole time the couple was eating.

After that incident, Barton telephoned Heath’s daughter and relayed her concern about his erratic behavior. Elizabeth took her father in for some tests on New Year’s Eve 2006. The doctor urged that Heath not be left alone. Elizabeth and her younger brother hired a part-time nurse and took turns spending the night at Heath’s apartment on Barrington Avenue.

But it was too late to stop whatever illness, physical or mental, was plaguing their father. Ten days later, on January 9, 2007, Laurence Heath hanged himself.

Laurence Heath in 2004.

*

“I don’t think he ever forgave himself,” said Elizabeth Heath. “I think he was just basically tortured.” Her half-brother agreed. “He was his own jailer,” Ken Heideman said, “and he was pretty miserable.”

One of Heath’s screenplays, unfinished and unproduced, dealt obliquely with the death he had caused. “I think he was too close to the subject to be able to write about it well,” said Joan Barton, “and so it never really worked.”

For over thirty years, Heath’s car bore a vanity plate that attempted a writer’s inside joke: 2BCONT. Like many in the movie industry with far less reason to do so, Heath had devoted his life to remaking his image into something he could live with.

“He was always reinventing himself,” Elizabeth Heath said of her father. “I think he always sort of thought that he could just give it another shot and do it even better this time.”

*

For updates, or to leave a comment or read comments left by others, visit my Classic TV History blog here.

Notes on Sources

Unless otherwise noted, all quotations are taken from the author’s 2008-2009 interviews with the following: Joan Barton; Walter Brough; O. D. de Ryk; William Froug; the late John Furia, Jr.; Walter Grauman; Elizabeth Heath (a pseudonym); Kenneth Heideman; Stanley Kallis; Stephen Kandel; Bruce Lansbury; and Tom Sawyer. Some background material has been taken from conversations with other writers and producers who knew Laurence Heath. Lila Garrett, Leanna Johnson Heath, Rick Heideman, and Godfrey Isaac (who still practices law in Los Angeles) declined requests for interviews.

Most details about the death of Dolores Heideman were taken from coverage of the killing reported in the Los Angeles Times, the Van Nuys News, and the Valley Times. (The indispensable Jonathan Ward, my leg man in Los Angeles, retrieved a number of clippings I might not otherwise have seen.) Though some of those accounts were lengthy and rich in detail, none were bylined. The modeling and acting career of Leanna Johnson, Heath’s third wife, was documented in some detail by the her home town papers, the Long Beach Independent and the Long Beach Press-Telegram.

Heath’s own book, By Reason of Insanity (New American Library, 1966), was consulted as a secondary source. Because Heath altered many facts in unpredictable ways in order to disguise his identity, only a handful of details were taken from the book without independent verification.

Most material about Sam Benedict comes from William Froug’s How I Escaped From Gilligan’s Island: And Other Misadventures of a Hollywood Writer-Producer (Popular Press, 2005). Patrick White’s The Mission: Impossible Dossier (Avon, 1991) was an invaluable resource for the section covering that series.

Photo Credits

All photos courtesy Elizabeth Heath except: 1955 wedding photo courtesy Ken Heideman; 5060 Shirley Avenue photo by Jonathan Ward; By Reason of Insanity dust jacket; frame captures from “Shock” and Blacula.

Copyright © 2009 by Stephen W. Bowie