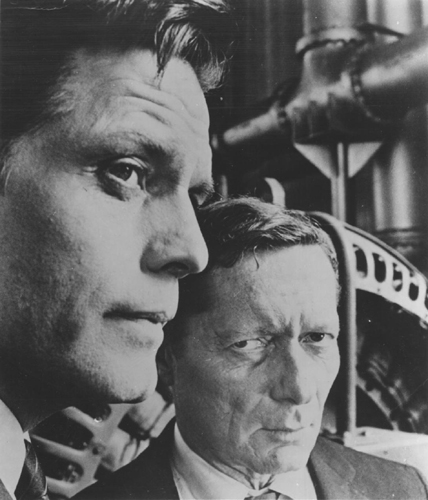

Diane Baker and Roy Thinnes in “Beachhead,” the series’ pilot

The Invaders: The Nightmare Has Already Begun

by Stephen Bowie

“The Invaders. Alien beings from a dying planet. Their destination: the earth. Their purpose: to make it their world.

“David Vincent has seen them. For him, it began one lost night on a lonely country road, looking for a shortcut. It began with a closed, deserted diner, and a man too long without sleep to continue his journey. It began with the landing of a craft from another galaxy.

“Now, David Vincent knows that the Invaders are here, that they have taken human form. Somehow he must convince a disbelieving world that the nightmare has already begun . . . .”

So intones the leaden voice that narrates the opening credits of one of television’s great forays into the realm of science fiction. Twenty-five years before The X-Files posited that the aliens are already among us and up to no good, David Vincent began his lonely two-year quest to save the world. Alternately pursuer and pursued, openly unhappy about his role as a modern-day Paul Revere and often pessimistic about his chances of success, Vincent proved a far more complex hero than 1960s television audiences were used to. He was the centerpiece of a sci-fi series more downbeat and more realistic than any that preceded it.

“The major thing that the show had going for it is the fact that we are all a little bit paranoid, and that it’s easy to identify with somebody who is a single man fighting the world,” said Invaders producer Alan A. Armer. “I mean, that’s what all real heroes are, if you look at the great myths and legends and the great stories that have been told. Frequently it is one person fighting the society, fighting the government, fighting an invisible force, and this is classic. And I think we all relate to that, because his job and his goal are so difficult to achieve. Conceptually, that’s what made the show strong.”

Diane Baker and Roy Thinnes in “Beachhead,” the series’ pilot

The Invaders’ successful format combined the sensibilities of two creator/producers who couldn’t have been more different. One was the unpredictable Larry Cohen, a brash wunderkind from the dying days of prestigious New York dramas like The Defenders, on the verge of leaving television to pour his twisted imagination into a string of low-budget cult horror films. The other was Quinn Martin, the steadfast, humorless king of sixties and seventies action television, overseer of a seemingly endless string of formulaic but exceedingly well-produced police and detective shows.

The Invaders began with Cohen, who freely concedes that his conception of the series was less an original idea than an amalgamation of several beloved pop-culture fixations of his adolescence. Fans of the show frequently point to Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the eery 1956 B-picture in which Kevin McCarthy discovers that his friends and neighbors are gradually being replaced by identical “pod people” from another planet, as the most obvious precedent for The Invaders. “That was one of my favorite movies when I was a child,” said Cohen, who also cites Invaders From Mars (1953) as an inspiration. The aliens of The Invaders apparently didn’t possess the technology to replace real people with identical facsimiles, and they employed glowing energy tubes called “regeneration chambers” rather than seed pods to affect their human form, but they were otherwise interchangeable with the Body Snatchers. Using subterfuge to infiltrate human society, the aliens relied on humans’ natural skepticism toward “crackpots” like David Vincent to protect them from anyone who stumbled onto their existence and tried to blow the whistle on their plans.

Invaders buffs often assume, since much of the same creative talent worked on both shows, that Cohen borrowed the series’ man-on-the-run format from The Fugitive, the 1963 hit starring David Janssen as a wrongly-convicted death row inmate who escapes to search for his wife’s killer. In fact, Cohen said, he took his cue from the Master of Suspense:

“Of course The Invaders was definitely in the same genre as The Fugitive: a man moving across America, in search of something, and in jeopardy. Really, to me, my idea was taken more from Alfred Hitchcock than it was taken from The Fugitive. I always liked the Hitchcock movie where the hero is in a situation where he’s the only one that knows the spies are operating, and no one will believe him. And when he takes the police back to the locale where he saw their operation, everything has been removed, there’s no more evidence, everybody lies and says that he was never there before.” Hitchcock made several picaresque thrillers in this mold, including The 39 Steps (1935) with Robert Donat, Saboteur (1942) with Robert Cummings, and of course North by Northwest (1959) with Cary Grant.

“That’s basically the Hitchcock formula, which he’s used over and over again, and it always seems to work and creates a tremendous amount of suspense, and you identify with this sympathetic character who’s really an underdog,” said Cohen. “I thought this was a good form and really hadn’t been used much in television. So that’s why I presented the show originally to Edgar Scherick at ABC.”

ABC was itself an underdog, a third-place network in a position to try an untested format in the hope of coming up with a surprise hit. Cohen decided to pitch his alien infiltrators idea as a different kind of soap opera, a hard-edged variant on the melodramatic and wildly popular Peyton Place, an early prime-time serial that ABC launched in 1964. According to Cohen, Scherick and his right-hand man Douglas S. Cramer (who, as head of Paramount Television, went on to oversee Star Trek) warmed immediately to The Invaders, albeit in a very different form.

“My original concept was to do The Invaders as a twice-a-week serial, something which the network borrowed from me and ended up doing with Batman. But that was originally my idea, to take two segments a week and have kind of a cliff-hanger in the middle,” recalled Cohen. “I was commissioned by them to write the pilot as a half-hour, and then I wrote about fifteen story-lines for future episodes of the series.”

Given the green light, Cohen sketched out the basics of what became The Invaders. He created the protagonist, David Vincent, a Santa Barbara-based architect who suddenly becomes a pariah after he sees a flying saucer and tries to warn a disbelieving public of the alien danger. His credibility ruined, Vincent gives up his partnership in an architectural firm and goes on the road, dividing his time between earning a living through menial labor and trying to gather tangible proof of the invaders’ existence. In the process Vincent becomes a quasi-famous object of public ridicule, and gains some hope in the form of contacts in the press and the military who, though skeptical, agree to examine with an open mind any evidence that he can produce.

As for the aliens, Cohen left their origins and characteristics a deliberate blank. “They were very intelligent, and very hard to kill, and very devious about hiding their identities and subverting themselves within the system,” Cohen said. Never during the course of the series did viewers learn what life on the aliens’ world was like, nor even, for that matter, the name of their planet or their species. But Cohen did devise some visual signatures that became the most recognizable aspects of the show: the regeneration chambers; the spontaneous combustion that immediately follows the death of any alien and leaves only a trace of ash in place of a body; the glowing disk that, when pressed against the back of the neck, causes a cerebral hemorrhage in a human; the aliens’ inability to feel pain and their lack of blood or a heartbeat. And of course there was the deformed pinky finger, an imperfection in some aliens’ human bodies that served to tip off Vincent as to their true identities.

Assured that his creation would in fact make it onto the airwaves, Cohen decided to practice a little subversion himself. He inserted an element of subtle political content into The Invaders, just as he had with his previous series, the Chuck Connors western Branded, about a Civil War soldier falsely labeled a coward.

“Branded was my way of doing the blacklist story on television, and The Invaders to me was a way of doing a show about the communist paranoia that the industry was just emerging from at the time. I thought, well, this is an interesting thing if we can take this paranoia and put it on the television screen and sell it to the television networks without them even knowing what they’re buying,” said Cohen.

Of course, The Invaders reversed the polarity of the blacklist era. In retrospect the American communist party seems like an ineffectual radical minority, feared and persecuted out of proportion; whereas on The Invaders the aliens really were plotting to take over the world. Rather than indulging their paranoia, the American people refused to see this true menace. Nevertheless, the structure of many Invaders episodes paralleled that of the I Led Three Lives-style commie-hunting movies and TV series, with David Vincent occupying a role similar to the tireless anti-Red investigator.

For Cohen, even the crooked little finger took on a hidden meaning. “The extended pinky used to be a symbol of effeminacy,” Cohen recalled. “You know, the effete [person] holding a glass of champagne with the pinky extended? When this show was done back in the sixties, the homosexual community was kind of a submerged, invisible community. People were living secret lives. I thought, here are these aliens living amongst society, keeping their true identities secret, their true selves secret, and this is funny because the pinky kind of symbolizes homosexuality in some way, and nobody will get the gag, but I’ll put it in there anyway.” This in-joke, inconsequential as it may seem, also relates back to the series’ witch-hunt metaphor, since at the height of the Red Scare gays were often inaccurately accused of being communists (and vice versa).

But once Cohen turned this material over to ABC, the network requested a change. Even though Peyton Place was at the height of its popularity, having expanded from two broadcasts a week to three, and the Batman craze had begun, Scherick and company opted not to produce the show as a serial. “I guess they just decided that it was strong enough to go with a traditional program policy,” Cohen suggests.

It’s also likely that ABC placed more faith in the already tried-and-true formula of the QM Production than in the longevity of the serial fad. “QM” stood for Quinn Martin, the son of a motion picture editor, who learned the film business as he grew up and entered television as a sound editor at Ziv, the production outlet responsible for Science Fiction Theatre, Highway Patrol, and other cheap syndicated fare. Moving to Desilu – where his wife, Madelyn Pugh, was one of Lucille Ball’s head writers – Martin made a name for himself by producing The Untouchables and turning it into a huge hit. Capitalizing on his newfound clout, Martin launched his own production company, offering up the police procedural The New Breed under the QM banner in 1961.

The New Breed, which lasted only a year, was a rare failure. By 1966, Martin had given ABC three big hits in as many years: The Fugitive in 1963, The F.B.I. in 1965, and in between them the already declining Twelve O’Clock High (which would bow out in the same week that The Invaders debuted). His production company was the hottest in town, and it continued to spawn massive ratings successes (of steadily decreasing creative merit) well into the seventies, among them Cannon, The Streets of San Francisco, and Barnaby Jones.

Quinn Martin was a notorious obsessive. On most sixties TV series, one or two producers oversaw the entire process of production, from the pitching of stories to the final dubbing of the music on each episode. But Martin compartmentalized his company, dividing the responsibilities for every series among four or five highly departments that rarely interacted with each other. “Every area on all of Quinn’s shows was carefully delineated,” said The Invaders’ post-production supervisor, John Elizalde. Added writer George Eckstein, “Unlike anybody else, Quinn had a production setup in which he had a preproduction operation and a post-production operation, and a producer very rarely saw a cut of the picture, [and] did not participate in the dubbing or the scoring.”

At QM, the department heads held the same responsibilities on all of Martin’s series simultaneously, including The Invaders. Adrian Samish supervised preproduction, approving budgets and art direction and occasionally getting involved with the scripting process. John Conwell was QM’s casting director, and Martin himself hired the directors. Arthur Fellows oversaw the editing of the film, while John Elizalde handled the scoring of music and dubbing of sound effects. Only the producer on each show was different, and, relieved of all other considerations, he was able to spend virtually all his time working with the series’ writers. “All he did was develop scripts,” said Eckstein. “All the producers were really just writers.”

The result of QM’s system was that it left Martin with virtually total control of all his shows. “Quinn was a benevolent despot, with the accent on the benevolent,” recalled John Elizalde. “If you knew what you were doing, he gave you very free reign.” According to George Eckstein, Martin “was always a gentleman, he paid very well, he was very good to his employees, and he was very creative.”

By contrast, said QM producer Anthony Spinner, “If it was a hit, may he rest in peace, it was Quinn Martin’s hit. If it was a failure, it was everybody else’s. And you were not to get your name too prominently mentioned in the trades or the newspapers. [QM] was sort of like a factory. There was only one person there who had autonomy, and it was Quinn Martin. He was a great friend and a terrible enemy, and you never knew which one he was going to be on any given day.”

Martin’s show’s all shared a highly distinctive visual signature. Each one was narrated by an almost impossibly deep baritone (most famously, Cannon star William Conrad on The Fugitive) who proclaimed over the opening credits that the series was “a QM Production.” Every episode was divided uniformly into a prologue, four acts, and an epilogue, and lest the viewer remain unaware of this neat schematization, a superimposed title announced the beginning of each act. The Invaders featured perhaps the most imaginative variation on this visual tic. After each commercial break, the picture reformed in the center of a blackout, spreading outward to cover the entire TV screen as if emerging from some alien black hole.

Martin’s greatest strength as a producer was his devotion to production values. Martin paid higher salaries to guest stars than any other company in Hollywood, often recruiting performers who rarely did television, and he shot on location extensively. “He demanded quality. When it was night in a scene, he’d shoot at night; he wouldn’t shoot it day for night,” said Invaders director Sutton Roley. “He spent some money. And he paid a little extra to directors, to writers, to everyone else to get that kind of quality.” As a result, Martin’s shows had a pristine look, with none of the drab sets or phony backlot exteriors that characterized series shot at Universal (The Virginian) or Paramount (Star Trek) during the same period.

On the other hand, Martin’s taste tended toward the pedestrian, and the story content of his series often exhibited a depressing sameness. His protagonists, with the exceptions of David Vincent and The Fugitive’s Richard Kimble, were always policemen or private detectives, and they were always unalterably heroic. Shades of gray occupied no space in Quinn Martin’s world. The Martin shows generally rivaled Dragnet in their unsmiling straightforwardness. “Quinn was notable for a lot of virtues, but one was not his sense of humor. You could never put much humor in. You had to be deadly serious at all times,” said Anthony Spinner.

Which leads one to the obvious question: Why would a quirky, paranoid, covertly political fantasy like Larry Cohen’s The Invaders attract Quinn Martin? The answer is probably a matter of pragmatism. According to Spinner, “Quinn had an exclusive contract with [ABC], and I think they just told him, ‘[If] you do this show, we’re going to put you on the air.’ Well, once somebody said to Quinn, ‘We’re going to put you on the air,’ I don’t think he cared what it was!”

Most of Martin’s associates concede that the TV mogul really didn’t understand The Invaders. “It was a departure for Quinn,” said Alan Armer. “He felt a little uncomfortable in that it wasn’t his bag. We all have certain areas that we feel secure in, that we feel we know how to do well, and I think Quinn didn’t feel that about The Invaders.”

But, in fact, Quinn Martin’s trademark seriousness was the final ingredient needed to make The Invaders a classic. It grounded the series in reality, providing a kind of credibility that made the show genuinely spooky and distinguished it from all its sci-fi contemporaries. “[The Invaders] was not very far out, by any means. It wasn’t like The Outer Limits, where you were on Pluto today and Mars tomorrow,” said John Elizalde, who worked on both shows. Irwin Allen’s kiddie fare (Lost in Space, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea) offered up silly cliches, and even the intelligent Star Trek resorted to Nazis-in-space or gangsters-in-space shows. But The Invaders, whose impeccably dressed aliens were so clean-cut they could pass for FBI agents, seemed just plausible enough to be possible. At its absolute best, it could be as scary as The Twilight Zone.

To launch the series, Quinn Martin scrapped Larry Cohen’s serialized pilot script and commissioned a ninety-minute teleplay from Anthony Wilson, recently the author of a well-received Fugitive two-parter (“Landscape With Running Figures”) which paired Kimble off with the one person perhaps more thoroughly tired of Kimble’s pursuer Lieutenant Gerard than he himself was: Gerard’s wife. Another Fugitive veteran, producer Alan A. Armer, left the David Janssen series to produce The Invaders, and regular Fugitive cameraman Meredith Nicholson took time out to shoot the pilot, which was entitled “Beachhead.”

“Beachhead” starts off with the familiar sequence of events that the opening titles of future episodes would recap in a truncated form. David Vincent, tired and lost amongst rural backroads, pulls over for some shuteye only to be awakened by the glowing lights of a landing spacecraft. When he brings the skeptical town sheriff (J. D. Cannon) back to the area, there’s no UFO, and Vincent’s insistence that he has encountered aliens from another planet earns him a stay in a sanitarium. Ultimately Vincent finds evidence of extraterrestrial activity in a small town near the landing site, but the discovery gets his best friend and business partner Alan Landers (James Daly) killed.

This initial installment introduced most of the motifs that became central to the series. The alien trick of making Vincent look like a buffoon in front of the authorities, as well as the ever-popular stiffened little finger, make their first appearance here. (But the first aliens Vincent meets, disguised as innocent-looking campers, also sport glowing silver eyes, which were never used again, apparently because the contact lenses irritated the actors’ orbs.) Diane Baker guest stars as the first incarnation of one of the series’ archetypes: the lonely single woman and potential romantic partner for Vincent, who may or may not be an alien temptress. Wilson’s script also establishes the bleak tone of the show, relentlessly severing Vincent’s ties with his former life through the incineration of his apartment by an alien assassin and, of course, the death of his partner.

“Beachhead” was cut down to fit into a regular hour timeslot when it was first broadcast in January 1967, and Alan Armer has said wistfully that in its original form the pilot constituted The Invaders’ finest and subtlest effort. The Museum of Modern Art screened the unedited “Beachhead” in 1969, but sadly it hasn’t been seen since. (Neither of its two VHS releases restored the pilot to its full 75 minutes.) As it stands, though, it’s a better-than-average episode, well-directed by Joseph Sargent despite the choppy pacing that resulted from the cuts.

“Beachhead” also showed off its star to good advantage. To play David Vincent, Quinn Martin had chosen one of the television heartthrobs of the moment, soap opera veteran Roy Thinnes. Born in 1938, the Chicago native began acting in high school and crashed New York in 1957, where he appeared on TV, in industrial films, and off-Broadway. After military service as an M.P., Thinnes moved to Los Angeles and married a then better-known actress, Lynn Loring, who had spent ten years as a juvenile lead on the daytime serial Search For Tomorrow (and who would guest-star in the Invaders segment “Panic”). In the meantime, the young actor racked up credits in various media – on stage in Genet’s “The Balcony” and Coward’s “Private Lives,” a small role in the film version of Lillian Hellman’s Toys in the Attic (1963), and lots of television guest shots. Thinnes became a member of Quinn Martin’s unofficial stock company, appearing on The Untouchables, Twelve O’Clock High, The F.B.I., and The Fugitive.

Thinnes’ big break came in the form of a two-year stint on General Hospital, starting in 1963. (Some of his General Hospital episodes have been subjected to ridicule on Mystery Science Theatre 3000). It was there that female viewers started to notice Thinnes’ rugged good looks – the thrice-broken nose courtesy of his days as a teenage street brawler – and his voluminous fan mail convinced ABC to use Thinnes to provide the testosterone quotient in its 1965 TV adaptation of William Faulkner’s The Long Hot Summer. Thinnes starred as Ben Quick, the role played by Paul Newman in the 1958 film of the same title (and his and the network’s press agents were quick to draw the comparison). Summer flopped fast, but Martin scooped up Thinnes, at $7500 a week, to play David Vincent in The Invaders.

Roy Thinnes proved a bit of a departure from the usual Quinn Martin casting mold. Martin preferred affable leading men like Paul Burke or Buddy Ebsen, whose easy temperament on the set conveyed an essential warmth to the viewer as well. “They were a certain kind of actor,” said second-season Invaders producer David W. Rintels. “They were not the Method actors. Stanislavsky was not big on our shows.”

Though not formally Method-trained, Thinnes radiated intensity and had an artistic bent. According to press materials used to promote The Invaders, he was also a painter, pianist, and published author. Though he was always courteous and professional, some crew members found Thinnes distant and intense – a reaction that may have carried over to the show’s audience, as well.

Many QM personnel were non-plussed by how seriously Thinnes took his role as a modern-day doomsayer. “Roy, as I recall, began to believe that there were invaders — that he saw them over Wilshire Boulevard with his then-wife once,” said Anthony Spinner. In fact, Thinnes did tell reporters that he and Loring spotted a UFO shortly before The Invaders debuted. The convenient timing smells of a publicity stunt but, according to Alan Armer, Thinnes “was a believer, and he believed in the series. I remember going down to the stage and talking to Paul Wendkos, who is a superb director, because Paul was making jokes about the concept of flying saucers and aliens being on the [earth], and I asked him please not to do that, that the lead in our series took the role very seriously. It was upsetting to Roy that members of the crew [were] kind of putting down the concept of the show and the idea of aliens being here.”

Thinnes himself described The Invaders as only a very narrow extension of reality. “We are theorizing with reality, theorizing as to who flies UFOs and why they are here,” the actor remarked in 1967. “I believe in unidentified flying objects and that covers a vast variety of possibilities that are now being investigated by many of the finest scientific minds in this country – with government funds supporting research.”

Both Thinnes and Alan Armer took the time to explore the real-life world of UFO phenomena, attending a convention of believers and speaking to individuals with stories similar to David Vincent’s. “We saw a lot of kooks,” recalled Anthony Spinner. “We interviewed people who claimed to have seen spaceships, or that we were doing very bad things and the aliens were very unhappy. They would seek us out and Alan, for some reason, would grant them time that we didn’t have. Maybe he was curious or amused.”

To score “Beachhead” and compose the Invaders theme, Quinn Martin turned to QM’s de facto music director, Dominic Frontiere. Frontiere began as an arranger for Twentieth Century-Fox and began writing music for television after he became a partner in Leslie Stevens’ independent production company Daystar. At the same time he was composing themes for Daystar’s Stoney Burke and The Outer Limits, Frontiere wrote the title music for Martin’s The New Breed and by virtue of that became the in-house conductor for virtually all of QM’s shows. In retrospect, Frontiere is probably best remembered for his complex, diverse work on the first season of the cult classic The Outer Limits, and it was probably this experience in the sci-fi genre that led Martin to assign The Invaders to Frontiere.

Unfortunately, Martin and Frontiere had a falling out over the initial batch of Invaders scores. “He had written an end credits [theme] that Quinn didn’t like and I didn’t like, and he wanted it to stay, and Quinn said no, so that was it,” said John Elizalde. As a compromise, Frontiere pulled out pieces of music that he had written for The Unknown, an unsold Daystar suspense-anthology pilot, and used them for both the opening and closing themes on The Invaders. “It had to be done very quickly, and we all liked [the Unknown score], so he released it,” recalled Elizalde. Since the public rarely saw unsold pilots, such practices were not uncommon; but The Unknown, in a slightly altered form, was telecast as the now-famous Outer Limits episode “The Forms of Things Unknown,” so television enthusiasts now have ample opportunity to compare the two scores.

Frontiere received credit for the incidental music in four of the earliest Invaders episodes. But in addition to writing original music, the composer again cannibalized bits and pieces of his earlier Outer Limits work. The love theme from “Beachhead,” for example, initially appeared in The Outer Limits’ “The Man Who Was Never Born,” and a haunting waltz from “The Forms of Things Unknown” crops up in several early Invaders (and also as the theme for a temporarily blinded Richard Kimble in the Fugitive segment “Second Sight”).

Original or not, Frontiere’s early Invaders motifs were moody, undeniably rich, and a major influence on all of the later compositions written for the series. “Frontiere created a little motto that was just a half-step thing. That was something that we used whenever we were aware that any of the characters in the story were aliens. You recall they had a little finger that stood straight out? Well, whenever you’d see that, or when they immolated, we [used that],” said second-season composer Duane Tatro.

Good as it was, the Invaders pilot did not sell the series. It didn’t have to. Midway through the filming of “Beachhead,” ABC surprised Quinn Martin with the news that The Invaders would be a flagship show in its “second season” of mid-year replacements. Martin’s sci-fi outing was slated to replace a pair of turkeys – the Phyllis Diller vehicle The Pruitts of Southampton and the comic western The Rounders – in its Tuesday 8:30-9:30 PM slot, and QM would have to have the show ready to debut in January 1967.

As The Invaders hurried into production, Martin made a few changes in his staff. Andrew J. McIntyre took over as the series’ regular photographer, creating a look that effectively blended the garish primary-color palette style popularized by Batman with shadowy, washed-out lighting more suited to The Invaders’ dark tone. Live TV veteran Anthony Spinner, creator of the Warner Bros. western The Dakotas and a story editor on QM’s Twelve O’Clock High, moved over to serve as The Invaders’ associate producer.

The series also suffered its first casualty. Larry Cohen had been involved with the production of the pilot but, as a QM outsider, soon found himself getting the big chill. “It became pretty clear to me from the outset that Quinn Martin really didn’t want Larry Cohen around, that Quinn Martin’s operation was more of a one-man operation and that I was too much of a maverick and too much of an independent person to be working under him,” Cohen said. “So he was happy to pay me the royalty and run the show . . . . I think I could have made a much better show than they did out of it, but at the time when I saw what was happening and I had a few sessions with Quinn Martin, I realized that there’d be no way the two of us were going to get along, so it might as well terminate as early as possible.”

Cohen did leave a legacy for The Invaders, though: most of the first season episodes are based on the story outlines he compiled for his initial pitch to ABC. Perhaps unjustly, Cohen never received a writing credit on any of these shows. “I was happy to get the ‘created by’ credit,” said Cohen, who remains philosophical about being maneuvered out of his own series. “Actually, because [Martin] came in, I got a very good deal from ABC. They revised my deal so they gave me a gross participation in the profits instead of a net participation, so that the show went into meaningful profits for me very quickly, and I’ve made money off the show all these years . . . . They [QM] did what they wanted to do, and I went off and did what I wanted to do, and made my own horror movies and my own science fiction.”

With the pressure of their January deadline looming, the Invaders producers scrambled to get an abbreviated season of 17 episodes into production. If Quinn Martin and company were inclined to do research into real UFO phenomena, there was no time. Unlike the later Project UFO and The X-Files, The Invaders never made reference to the wave of real-life flying saucer sightings that began with the famous 1947 Roswell, New Mexico incident.

Alan Armer and Anthony Spinner did attempt to seek out established genre writers to contribute to the series, but their efforts proved largely fruitless. “We brought in some top science fiction writers who couldn’t do it at all – Ted Sturgeon, I remember, was one we talked to – and they couldn’t come up with a story to save themselves, which was kind of fascinating,” said Spinner. Sturgeon did receive a partial story credit on the creepy “The Betrayed,” and in the second season sci-fi novelist (and Star Trek writer) Jerry Sohl contributed a pair of scripts. For the most part, though, the first batch of Invaders episodes were penned by established television writers, many of them veterans of earlier QM shows, who were more comfortable with the show’s earthly elements than its extraterrestrial ones.

Perhaps for this reason, The Invaders initially hewed close to Larry Cohen’s idea of keeping the aliens and their gadgetry off-screen or in disguise as much as possible. Press materials for the show emphasized the guessing-game aspect of the aliens’ stealthy nature: “Who are The Invaders? A person riding on the bus this morning could be one of them. And the postman might be one. Or the dentist,” cautioned radio ads for the series.

“After the pilot, I offered to build a spaceship that we could photograph – a miniature,” said John Elizalde. “And Quinn said, ‘Oh, no, John, we’ll never see that spaceship again.’”

The early episodes did dwell on the aliens’ background and methods to some extent, however, as they fleshed out the basics of Cohen’s premise to set the ground rules of the Vincent vs. Invaders conflict as plausibly as possible. In writing the narration that would accompany the opening titles of all the post-pilot episodes, Anthony Spinner discovered that no one had bothered to examine the reasons behind the titular invasion.

“I said, ‘Well, why are they here?,’ and I don’t think anybody had a great answer,” Spinner remembered. “I said, ‘Well, I guess their planet must be dying, isn’t that the old cliche? They gotta go someplace?’ ‘Uh, yeah, that’s fine, why don’t you write an opening?’ So, I wrote the opening.”

If the sci-fi trappings of the series were to be short on creativity, they would at least be long on credibility. Subsequent episodes established details about the aliens that may have struck science fiction enthusiasts as familiar, but never far-fetched. “The Mutation” emphasizes that the aliens lack any emotion whatsoever, and thus act utterly without compassion in dealing with humans. The episode’s storyline takes “Beachhead”s is-she-or-isn’t-she dilemma a step further. Vincent’s love interest, stripper Vikki (Suzanne Pleshette), admits that she’s alien early on but insists that she’s different, can feel compassion, and wants a truce between her people and ours. The question for the audience, and Vincent: can she be trusted?

“Vikor” introduces the regeneration chambers that maintained the aliens’ human form – without periodic visits to the big glowing tubes, the aliens burn up. “The Ivy Curtain” shows a private school where new alien arrivals receive their indoctrination, a detailed crash course in human behavior right down to (in a hilarious scene) the correct counterculture lingo for those invaders lucky enough to go undercover as hippies. (This, too, was a bit of Cold War allegory, parallelling the training courses in western esoterica for the communist infiltrators thought to exist in the Soviet Union.) In “Wall of Crystal” we learn that oxygen is lethal to the aliens in their natural form. “The Condemned” gives us a glimpse of an alien air traffic control center, where incoming saucers are dispatched to various parts of the world.

“Vikor” was also the first segment to employ a motif that originated in Larry Cohen’s notes and that The Invaders would turn to again and again: the human collaborator who, for whatever ill-conceived motive, assists the aliens and then must pay for his or her mistake. In this episode, Jack Lord plays George Vikor, an industrialist who turns traitor because he feels bitter and betrayed by his own kind – though Vikor won medals for his Korean War heroism, no one would give wounded ex-soldier a job or a loan when he mustered out of the army.

Jack Lord and Alfred Ryder in “Vikor”

In a surprisingly brutal finale, Vincent calculatingly arranges Vikor’s death, framing the man with evidence that Vikor is a government agent and thus ensuring that the aliens will murder him. Only rarely did The Invaders take the chance of showing Vincent in such an unsympathetic light, and “Vikor” establishes beyond a doubt that the series’ hero is a more fanatical and uncompromising one than The Fugitive’s always-noble Dr. Kimble.

In “The Ivy Curtain,” the second (and superior) collaborator episode, pilot Barney Cahill’s motive for flying for the aliens is less convoluted and more convincing: Barney (Jack Warden) fears for his life, and his greedy wife (Susan Oliver) wants the cash that the invaders proffer. Here, the outcome is more in keeping with the Quinn Martin code of ethics. Betrayed by his wife, Barney comes to his senses and sacrifices his life in a kamikaze raid on an alien stronghold.

The best of the first season episodes were those which tried to push the series past its science fiction conventions and into the realm of horror. The otherwise mediocre “Genesis” opens with a frightening teaser in which a highway patrolman (Phillip Pine) at a routine traffic stop peers into the back of a station wagon and loses his mind when he happens to see the naked form of an alien without its human disguise – a sight which remains, naturally, off-screen.

The unrelentingly grim “The Leeches” describes in surprisingly graphic terms the tortures heaped by the aliens upon captured human scientists, and again the worst is left to the viewer’s imagination. “The Betrayed” drifts into melodramatic excess (not one but two martyred humans die in David Vincent’s arms), but Vincent’s hushed conferences with the paranoid electronics expert Neal Taft (Norman Fell) build a deliciously nerve-tingling suspense as the episode progresses toward the inevitable arrival of the alien death squads. Moments like these were infrequent, as if the producers never realized that this was perhaps the most promising direction in which to take The Invaders. But they were the scariest stuff on television since The Outer Limits, and they anticipated the relentless paranoia of The X-Files and 24.

The strongest of the first seventeen Invaders is probably “Moonshot,” in which the aliens infiltrate the first manned moon landing in order to safeguard an alien lunar installation that NASA has spotted in reconnaissance photos. For once, the aliens’ actions are clearly defined and plausibly motivated, and despite certain similarities to the Twilight Zone episode “The Parallel,” “Moonshot” is a taut suspense piece with an excellent cast. Among other things, this episode introduces a device that the aliens use to temporarily simulate a heartbeat, putting to rest the nagging question of how they managed to integrate themselves into so many facets of society without ever having to take a physical.

A final first season standout was “The Innocent,” which offers a rare glimpse into David Vincent’s personal life. Co-written, like “Moonshot,” by John W. Bloch (no relation to Psycho author Robert Bloch), “The Innocent” delighted science fiction buffs by casting Michael Rennie, famous for his role as the noble extraterrestrial Klaatu in The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), as the alien leader Magnus. In a dream sequence that Magnus engineers to convince David Vincent that the aliens are actually working to help humanity, we meet the architect’s old flame Helen (Katherine Justice) and see a facsimile of his unrealized dream: the conversion, through cutting-edge engineering technology, of a barren valley into a lush paradise.

Sutton Roley, one of the few television directors to impart a truly cinematic look to his work, helmed both “The Innocent” and its immediate predecessor, “Quantity: Unknown.” In “The Innocent,” he uses wide-angle lenses and bleary soft-focus to create an otherworldly look to the aliens’ faux paradise, which was actually the picturesque Rossmore Leisure World, a home for the retired in Laguna Hills, California. Roley also staged an homage to The Invaders’ Hitchcockian roots: a scene, almost identical to one in North by Northwest, in which the aliens force liquor down Vincent’s throat and put him behind the wheel of a moving car, to face either death or a drunk driving charge.

“[Roy Thinnes] had just had his teeth capped, and he was a little concerned about doing that,” revealed Roley. “He was very fearful that the actor was going to jam the bottle into his mouth and break his capped teeth. Anyhow, we did it, and it worked okay.”

In between inventive outings like “The Innocent,” however, The Invaders in its first season churned out a fair number of pedestrian clinkers. In retrospect, the series’ writers seem in many cases to have shared Quinn Martin’s failure to fully grasp the more far-out aspects of the show. “They were mostly writers that Alan had used on The Fugitive, and had been sort of house writers for Quinn Martin,” said Anthony Spinner of Invaders authors like Dan Ullman, Don Brinkley, and John Kneubuhl. “They just couldn’t handle this show.”

Typically, Alan Armer would meet with the writer of any given episode for a lengthy session in which the structure of the script was worked out in detail. “I remember the story conferences as being endless, and they were driving me crazy, because I wasn’t used to sitting with writers and Alan for three and four hours, talking about script,” said Spinner. “We all got covered with sweat trying to think these things out,” said writer Jerry Sohl. Armer’s influence on the content of the stories turned The Invaders toward formulas the producer had used during his Fugitive days.

Many of the early Invaders scripts relied on the pseudo-anthology format that drove The Fugitive. In a typical episode, Richard Kimble’s ongoing pursuit/flight quest usually took a backseat to the dilemma of a guest character, on whose behalf Kimble favorably interceded, even at the risk of capture. The Invaders tried to adapt this structure to episodes like “The Leeches,” in which the aliens’ efforts to kidnap a leading scientist shared screen time with a cliched love triangle between the scientist, his wife, and his best friend; “The Betrayed,” which opens with Vincent inexplicably in love with a pretty but rather dull blonde; or “The Condemned,” which focuses more on a father-daughter reconciliation than on the father’s efforts to fight the aliens who have taken over his factory.

Dr. Kimble’s do-gooderism sometimes strained credibility, but the irony of Kimble solving others’ problems but never his own was always rich. In The Invaders, though, the fate not just of one man but of the entire world was at stake, and any purely human conflicts seemed ludicrously trivial in comparison to David Vincent’s quest to expose the aliens.

Another problem was the lack of genre expertise possessed by Armer’s crew of writers. In “Genesis,” the storyline about an alien being somehow created in a Seaworld tank is so crammed with mumbo-jumbo as to make no sense at all. Writer John Kneubuhl penned some of the strongest Fugitive scripts, but his approach to The Invaders was to have the aliens hatch far-fetched plots to take over the world – a plague of super-locusts in “Nightmare,” a weather-controlling machine in “Storm” – that were completely at odds with their well-established method of conquering through infiltration. Ullman and Brinkley’s “Wall of Crystal,” in which Vincent confronts a brother who believes that the aliens are a figment of David’s imagination, is a direct lift from the Fugitive segment “Home Is the Hunted,” where Richard Kimble discovers that his brother secretly doubts Kimble’s innocence.

Even the best writers often found themselves hamstrung by a handful of acute flaws in the series’ premise. The Invaders depended heavily enough on fantasy that almost every episode gave rises to minor questions of logic – why, for example, didn’t Vincent simply shoot every alien he ever glimpsed in public, and thus force people to believe their own eyes as they saw the dead invader disintegrate? As Variety pointed out in its initial review of the series, “This kind of pulp fiction you just have to accept and enjoy for its profound innocence.” But there was one credibility gap so profound that the show’s production staff grappled with it virtually every week.

In short: why didn’t the aliens simply kill David Vincent? They vastly outnumbered and overpowered him, and yet every week they permitted the troublesome architect to foil their immediate plans to overtake the earth and almost expose them for good. Occasionally, as in “Vikor,” Vincent would prove so obnoxious that the aliens would try to off him, but always by the following week the bounty on his head had apparently been lifted.

“How many times could they not kill him?” asks Anthony Spinner, who struggled to come up with non-lethal ways for the aliens to interact with their nemesis. “In the one I wrote [“The Experiment”], they brainwashed him, and in another one we had Michael Rennie telling him what great people they were. I mean, there was a limit to what I thought we could do with it.” Other first-year episodes had the aliens impugning Vincent’s sanity, holding his brother hostage, or threatening to kill an innocent woman and child unless Vincent discredits himself. But these were stopgap measures, designed to postpone the question – why not just kill him?

The solution the writers ultimately devised and held to, one that always hovered on the outskirts of plausibility, was that Vincent’s notoriety as a crackpot had become so great that his death under mysterious circumstances would actually lend credibility to his claims of an alien conspiracy. It was a serviceable answer that cleared up an nagging continuity problem – in some episodes (“Vikor,” for example) Vincent is able to go undercover among the aliens or inside some top secret government installation for long periods of time without being recognized, whereas in others (like “Moonshot”) the invaders identify him almost immediately. The sturdiness of this particular plot point was proved decades later, when The X-Files invoked it as an explanation for why the Cigarette-Smoking Man and his confederates killed off many of Agent Mulder’s confederates and family members, but never Mulder himself.

The Invaders debuted on January 10, 1967, to mixed reviews and reasonably high ratings. But its initial success was a small-scale repeat of the previous winter’s Batman craze. Viewer interest peaked quickly and the show’s Nielsen numbers began a steady decline as the year wore on. As with any of his series that had yet to prove itself a hit, Quinn Martin monitored the situation closely. “His script notes came down. They were never from him. They were always from Adrian Samish, but we always knew that these were Quinn’s notes and this was his hatchet man,” recalled Anthony Spinner. “And you couldn’t really debate his hatchet man, because he had no authority, so most of the time I wound up making all of Quinn’s changes, for better or for worse.”

Though they acknowledged the script problems, Martin and Alan Armer also suspected that there was an even more serious factor that was keeping audiences from sticking with The Invaders – the show’s leading man. “He tended to play the role as if the world were against him,” said Armer of Roy Thinnes. “Quinn and I discussed that at some length. With any series, the producer is looking for a kind of charm or magnetism that makes the audience get involved with [the star]. But rather than playing vulnerability, which is what David Janssen was playing in The Fugitive, he was playing almost a surly attitude that was off-putting, that I don’t think made people care about him.” Two years before, Quinn Martin had gotten rid of an actor for precisely the same reason, replacing the brooding Robert Lansing with the blandly likable Paul Burke as the star of Twelve O’Clock High. No doubt Martin considered a similar switch on The Invaders, but ultimately Thinnes kept his job.

“We had lunch a couple of times, discussing what a leading man has to have in a series – all of these things that are going to make the audience care about you and root for you and like you,” said Alan Armer. “You have to find something in [a series’ protagonist] that you can get involved with. And it was hard with Roy. I think that was one of the factors that worked against the show, although there were others.”

Armer is right – David Vincent usually did come across as surly, brusque, impatient, and even condescending. In a way, Thinnes’ take on the character doesn’t make sense – one would think that Vincent would want to be as charming as possible when trying to convince disbelievers of his far-fetched story. On the other hand, the world was against David Vincent, and it is logical that the daily grind of risking one’s life in an ongoing battle with superpowerful extraterrestrials would tend to make a man tense and irritable.

In any case, Thinnes’ portrayal of the character was courageous and often supported by scripts which called for Vincent to commit some pretty unsympathetic acts. In “The Innocent,” Vincent is reluctant to capitulate to the aliens, even after they threaten the life of an innocent mother and child; indeed, he goes so far as to argue with the boy’s father as the man pleads for the life of his son! In “Nightmare” and “The Pit,” Vincent is churlish when questioning witnesses to alien activity; in “The Trial” he grows verbally abusive with a private detective in his employ; and when in “Ransom” his alien-fighting activities place the health of a sick old man in jeopardy, Vincent responds with a disinterested, “Sorry.” Even his allies don’t like him – in “Task Force,” a newspaper publisher who pledges support to Vincent’s cause calls him “rude, hostile, boorish, and arrogant.”

David Vincent may have been television’s first really nasty, hard-to-like antihero. The term antihero had previously been applied to characters like Richard Kimble and Route 66’s Tod and Buz because they in some way defied the establishment, but their rebellious attitudes didn’t get in the way of their basic cuddliness. To his credit, Roy Thinnes resisted the producers’ pressure and never significantly altered his interpretation of the character; if anything, David Vincent grew more callous and brittle as the series progressed. “Quinn and I were pulling him hopefully toward a character that would be more sympathetic, and he was unable to go that way,” said Alan Armer.

According to Anthony Spinner, Alan Armer himself became a scapegoat for the series’ initial failure to catch on. “Quinn was dissatisfied with the way the show was going. I got a surprising phone call to have lunch with Quinn and Adrian Samish. I had no idea what the lunch was about,” said Spinner, who met with Martin and Samish at the former’s famous noontime hangout, the front booth in the venerable Hollywood Boulevard eatery Musso and Frank’s. “It was proposed that I take over the show from Alan, because Alan wasn’t doing a good job. I refused. We went back to the lot, and Quinn saw me alone in his office, and said that Alan was going to be fired one way or another, so I might as well take his job. And again I refused. Alan was a pretty good friend; I just didn’t want to be promoted over the body of a friend. Quinn wasn’t too happy.”

Alan Armer, who believes that Martin was too loyal to stab an employee in the back, refutes this story. In any case, it was Armer who stayed on with The Invaders, and Spinner who departed. “I knew by the end of that first season [that] I’d better get another job, because Quinn was not a man you said ‘no’ to,” recalled Spinner, who went on to produce seasons of The Man From UNCLE and The Mod Squad before returning to the QM fold to oversee several of Martin’s shows in the seventies.

Ratings aside, ABC had enough faith in Quinn Martin to order a full slate of 26 episodes for the 1967-68 season – and almost immediately had cause to doubt their decision. In interviews Alan Armer had spoken of fleshing out David Vincent’s character and making other improvements, but The Invaders’ second season opened with a quintet of mediocre entries that seemed like particularly bad leftovers of the first year’s semi-anthology formula.

“Condition: Red,” the season premiere, starts with the promising set-up of a key NORAD officer married to an alien temptress, but descends quickly into routine action fare as it artfully dodges the thornier questions suggested by such close interspecies relations. Variety’s review wondered “just why these superhuman beings have to worry about such trivia as radar,” and correctly predicted that The Invaders would be slaughtered by its CBS competition, The Red Skelton Hour.

The second outing, “The Saucer,” proved even more odious as it pulled off the most obvious Fugitive steal yet, even down to the casting. Like The Fugitive’s 1967 episode “The One That Got Away,” it featured Anne Francis and Charles Drake as a pair of embezzlers fleeing the law – a shame, since their travails are much less interesting than the suspense plot in which Vincent captures a downed spaceship. (This was an example of a curious trait of Martin’s, whose taste in casting was so unimaginative that he would typecast actors in near-identical roles in different shows, or duplicate groupings of three or four actors in different episodes of his series. “I used to say I could [open] TV Guide, look at the cast of a QM show, and tell you the plot,” said frequent QM director Ralph Senensky.)

“The Saucer” gave viewers their first glimpse (aside from a brief shot in each week’s opening credits) inside an alien ship, marking the peak of a trend toward the overuse of generic sci-fi trappings. The segment is filled with alien stormtroopers in drab green coveralls, who retain their human form but blow their cover with silly-looking rayguns.

The spacecraft itself, which Quinn Martin had originally thought would only be seen in the pilot, is featured more prominently in “The Saucer” than in any other episode. “There were a lot of opticals to be done, and that was a large part of the budget,” said John Elizalde of the increased use of special effects. Only the pentagonal base of the spaceship, with its triangular legs, was a live prop; the saucer part of the vessel was matted in later under the supervision of visual effects man Darrell A. Anderson.

The best part of “The Saucer” is its original score, the first of six written for the show by The Invaders’ new composer, Duane Tatro. Since Dominic Frontiere’s stormy departure, only three scores had been commissioned for the series, one each by Richard Markowitz, Sidney Cutner, and Irving Gertz (“Quantity Unknown,” “Condition: Red,” and “The Enemy,” respectively). Tatro caught the attention of John Elizalde while ghostwriting for Markowitz (a common practice at the time), and “The Saucer” became his first credited composition for television. “I did just a little touch of jazz in it, and they were not at all used to that,” said the Paris-trained Tatro, a former member of Stan Kenton’s band, of broadening QM’s musical horizons. “Not a big thing, but they were a little bit dubious about it when they first heard it on the scoring stage. And of course I was very apprehensive because it was the first time I ever had an assignment of my own. [But] they couldn’t get me going on the next one fast enough.”

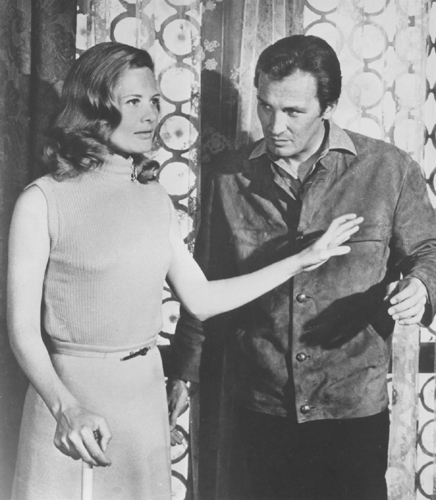

Shirley Knight and Roy Thinnes in “The Watchers”

The abysmal “The Watchers” rehashed the motivations of yet another human collaborator. Cobbled together by a committee of three fine writers – Twilight Zone veteran and Waltons creator Earl Hamner, The Outer Limits’ Meyer Dolinsky, and Star Trek’s Jerry Sohl – the episode nonetheless trots out the most shopworn Quinn Martin cliche of all, the noble blind girl (here played by Shirley Knight).

“Valley of the Shadow,” by default the best of these early second-year shows, again had the aliens blackmailing David Vincent into betraying his own cause to spare the lives of innocents. “The Enemy” redid another Fugitive (“The End Is But the Beginning”), this time with the variation of casting a wounded alien (Richard Anderson) in the Kimble role and Vincent as his obsessed pursuer. Barbara Barrie played a reclusive single woman who becomes mother-figure, protector, and nurse to Kimble/the alien in both episodes. “The Enemy” tantalizes the audience by having Anderson’s character gradually revert back to his alien form – an apparent breach of continuity, since early episodes had clearly established that badly wounded aliens disintegrate almost immediately. (The alien’s desire for individual self-preservation also runs counter to the suicidal fealty to their cause that most captured or exposed invaders displayed throughout the series.) In any case, the makeup used on Anderson was unimpressive, and viewers were no doubt disappointed by the only glimpse they ever got of the aliens’ natural appearance.

If “The Enemy” was a low ebb for the series, Martin and company made up for it the next week by telecasting the series’ most intelligent, and arguably its best, episode. “The Trial” introduces Charlie Gilman, Vincent’s buddy from Korea (a bit of a stretch, since Thinnes was fifteen when the Korean War ended). Gilman spots an alien in his home town of Lincoln City, but before Vincent can identify the invader Gilman kills him. Gilman is placed on trial for murder (with the prosecution contending that he disposed of the body in a nearby furnace), and Vincent rushes to his defense by testifying in open court that the dead man was from another planet, uttering the classic line, “I understand the definition of murder to be the killing of another human being. Fred Wilk was not a human being!” When it develops that Gilman’s wife was formerly married to the dead alien, “The Trial” leaps headlong into the territory skirted in “Condition: Red,” discussing with surprising frankness the prospect of sexual relations (or the lack thereof) with an extraterrestrial.

The episode offers a compassionate, non-judgmental portrayal of a woman who bore a child out of wedlock, as well as some thoughtful speculations on the implications series’ premise. At one point, for example, Vincent wonders if Gilman is taking advantage of his invader rhetoric to fabricate a fraudulent defense for murder. And in a rare reference to Larry Cohen’s intended parallel between the aliens and the 1950s Communist witch-hunts, a private detective refers to the dead alien as “a card-carrying member from outer space.”

“The Trial” even contains moments of ironic humor at Vincent’s expense. In one scene, the prosecution produces the dead alien’s parents; after they testify, Vincent confronts them in the deserted courtroom hallway. “You’d better come with me,” he said. “I’m afraid we can’t, David,” the false Mrs. Wilk replies, as she and her husband swallow suicide pills and disintegrate. A second later, the district attorney exits the courtroom, spots the befuddled Vincent, and gloats, “I’d say we’ve kind of got you by the ears!”

Best of all, “The Trial” is one of the few episodes that successfully carries out Larry Cohen’s idea of keeping the viewer guessing as to which of the principal characters is a disguised alien, throwing out several clever red herrings along the way.

Don Gordon and Lynda Day in “The Trial”

Amazingly, this sophisticated script was born of desperation and cranked out at the last minute. “We were crazed. Somebody had been supposed to submit a script, and it didn’t come and we had to get one into production right away,” said David W. Rintels, Anthony Spinner’s successor as associate producer, who co-wrote “The Trial” with QM contract writer George Eckstein.

“We did that in about a week,” said Eckstein. “He did two acts and I did two acts, and then we exchanged and did rewrites on each other’s, and it got put together. It was also supposed to be, since a lot of it’s in the courtroom, on a short schedule [to save money].”

“The Trial” kicked off a string of top-notch episodes. “Dark Outpost,” similar in some respects to The Outer Limits’ extraordinary “Nightmare,” serves up a clever parade of illusions as the aliens use hallucinations to trick Vincent and a group of archaeology students, held captive in a desert installation, into cooperating with them. Author Jerry Sohl implies that the students ally themselves with Vincent more readily than do most adults, because of their distrust toward the establishment figures that the aliens imitate.

“The Spores” was pure fun, a segment modeled on the vignette-structured episodes of The Fugitive (in which a different set of characters dominated each act), that set Vincent and menacing alien Gene Hackman against each other in pursuit of a metal case full of alien plant-seeds. “They were looking for a sound for the spores, and Elizalde had the idea in post-production – he got recordings of seagulls and played them backwards,” recalled Duane Tatro.

Diana Hyland in “Summit Meeting”

“Summit Meeting” brought Michael Rennie back as another alien and took the action to an international level, with a storyline about a plan to assassinate a group of world leaders at an upcoming peace conference. The first half of The Invaders’ sole two-parter is a fast-moving romp with a truly epic feel, featuring a chase through a hippie art gallery, a pounding martial score assembled out of stock music, and even a tongue-in-cheek reference to Quinn Martin’s The Untouchables. Sadly, the second part of “Summit Meeting” falls flat as it turns into an endless cat-and-mouse chase through an underground military installation. The sets are cheap-looking and the usually reliable Don Medford, who claimed he hated working on The Invaders, directs without inspiration. The high point of part two is the scene in which an exposed alien operative (Diana Hyland) tries to sell Vincent on the advantages of having no emotions. Mr. Spock, alas, was far more convincing.

In the midst of such escapist fare, The Invaders’ newest arrival had begun to usher in a subtle but constructive shift in the series’ tone. David Rintels was a young, progressive writer who went on to win three Emmys for his made-for-television movies, among them Fear on Trial (1975) and Andersonville (1996). Under his tenure, The Invaders began to tackle some political and social issues of the time, making use of the allegorical potential inherent in its sci-fi premise. The central character in “The Enemy” was a nurse who had witnessed so much horror in Vietnam that Vincent’s aliens paled in comparison. “The Captive” takes place in a Russian embassy and invokes the spectre of the Cold War. “The Prophet” and “The Miracle” criticize religion, obliquely but cannily. In the former an alien (a memorably hammy Pat Hingle) masquerades as an evangelist, delivering sermons designed to prepare earthlings for the coming invasion; one character, in the parlance of the times, describes religion as “just another trip.” In “The Miracle” a naive girl (Barbara Hershey, impossibly young) mistakes an alien’s death for a sign from God.

“The Vise” rather bizarrely combines alien intrigue with race relations, incessantly referencing the Detroit riots as well as Vietnam. Lacking an appropriate sensitivity toward racial awareness, the invaders make some serious errors when disguising one of their own as a black man: his fictitious background fails to reflect the pre-1950 segregation of the U.S. Army, and worse yet his palms are just as dark as the rest of his “skin.” In the funniest moment of the entire series, a group of indignant ghetto residents assail an alien “cop” who tries to arrest Vincent without first reading him his rights!

Rintels’ favorite of his own Invaders scripts is “The Peacemaker,” a Vietnam allegory that shows the aliens in a much more sympathetic light than usual. David Vincent brokers a peace conference between the aliens and the U.S. military; surprisingly, both the aliens and Vincent himself reluctantly concede that an armistice between the two species could be possible. The truce falls apart not due to alien treachery, but because of the crazed actions of a war-mongering general (James Daly) who tries to drop a nuke on the alien leaders who emerge for the negotiations. (“The Peacemaker” marks the third appearance of Alfred Ryder as an ultra-important alien leader, the only individual invader whom Vincent encounters more than once during the course of the series. In “Vikor” Ryder’s character was referred to as “Mr. Nexus,” but in a gaffe Vincent calls him “Mr. Ryder” here.)

Phyllis Thaxter and James Daly in “The Peacemaker”

Not all of these topical episodes were successful. “The Peacemaker” comes across as strident, and “The Enemy” and “The Miracle” are muddled . “‘The Prophet’ was a show [the producers] didn’t have a lot of faith in,” said Duane Tatro. “It didn’t quite come off the way the had expected when they shot it, and they presented it to me. I was very enthusiastic about it because I saw it as a kind of mysterious, tambourine type of mood. I saw a dimension, perhaps, that had not been considered.”

The increasing issues-consciousness of The Invaders was part of a larger campaign to make the series more adult-oriented. ABC pushed the show back into the Tuesday 10:00PM slot – perhaps unwisely, since its most devoted following probably consisted of kids and teens who had graduated from the cartoonish Irwin Allen shows.

With the time slot change, The Invaders started to take itself even more seriously. David Vincent, often eschewing his comfy gold sports jacket in favor of a briefcase and a three-piece suit, began to look more like a character on The F.B.I. Even the aliens became more deadpan, as the producers quietly discarded their most famous trademark — the crooked little finger, which rarely appeared in the second season.

But the biggest change came in the thirty-first episode, “The Believers,” in which David Vincent finally gave up his solo fight and joined with a consortium of wealthy and influential Americans who had all encountered the aliens first-hand. Character actor Kent Smith joined the cast as Edgar Scoville, a well-connected electronics manufacturer and government defense contractor who leads the group. Smith, who had guest starred as a NASA official in the first season’s “Moonshot,” had been a minor leading man during the 1940s, best known for starring in the Val Lewton horror classics Cat People (1942) and The Curse of the Cat People (1944) and for playing Peter Keating, Ayn Rand’s apotheosis of mediocrity, in the film version of The Fountainhead (1949).

“He was all right, but he was such a weak actor. He always played weaklings in the movies, and he just didn’t have much force or energy in the part,” said Larry Cohen. Indeed, Smith failed to make much of an impression in The Invaders, but it was as much the writers’ fault as his own. Woefully underwritten, Edgar Scoville usually appeared in only two or three scenes in each episode to offer encouragement or information to David Vincent. The audience never learned of Scoville’s experiences fighting the aliens before he assembled the Believers, or anything else about him, for that matter. Scoville functioned as a plot convenience, a way of explaining how Vincent raised money to fight the aliens and how, in spite of his reputation as a nutcase, he managed to attract the attention of important goverment officials and military brass.

Hawaiian Eye star Anthony Eisley also came aboard, playing Vincent’s Believer friend and sometime sidekick Bob Torin. Eisley’s Invaders stint did not last long. The luckless Torin saw his wife murdered by the aliens in “The Believers” and was himself killed off in his second appearance, “The Ransom.” Lin McCarthy portrayed Believer Archie Harmon, an army colonel, in the episodes “Counterattack” and “The Peacemaker” before he, too, met his maker at the hands of the aliens.

Eisley and McCarthy were both rather colorless actors, QM favorites and recurring special agents on The F.B.I.; their appearances on The Invaders suggested a perhaps subconscious impulse on Quinn Martin’s part to send in the Bureau to do a little alien-fighting. Aside from these two, the roster of Believers, who were seen infrequently after their introduction, changed with each new episode.

“The Believers” was one of the best episodes of The Invaders. The basic story was standard stuff, with Vincent captured and taken to an underground interrogation center after a sneak alien attack on the Believers. He escapes with the aid of Elyse Reynolds, a psychologist whose brother died at the aliens’ hands; but when Elyse asks to join the Believers, Vincent suspects that their getaway was too easy and that the young woman is actually an alien spy.

Carol Lynley and Roy Thinnes in “The Believers”

Carol Lynley turns in an excellent performance as Elyse, and a suspenseful finale in a deserted bus station represents director Paul Wendkos’ best work for the series. But it is Barry Oringer’s teleplay that takes The Invaders’ grim tone and its paranoid outlook to a new level. The script contains multiple tricks and betrayals, and like Vincent the audience is never certain if Elyse can be trusted. Vincent’s reluctance to become emotionally involved with her gives viewers a rare look at the toll that his lonely, alien-hunting existence has taken on him. Most interestingly, the formation of the Believers seems to raise the stakes of the struggle between aliens and humans. During the course of the episode, the aliens murder five Believers, suggesting that Scoville’s group will strike them as a more serious threat than the lone Vincent, and that a new take-no-prisoners approach will apply. Vincent acknowledges the stepping up of his war in a speech to Elyse in which he urges her to carry on if he is killed.

To call “The Believers” a renaissance for The Invaders is a bit of an overstatement. The series’ revamped format showed a lot of promise in this initial installment, but the story potential of the Believers was never again fully capitalized upon. Making Vincent a team player was a logical, almost an inevitable, step. In virtually every episode, the architect convinces one or two ordinary people of the truth of his claims, and they usually pledge to carry on their own fight against the aliens. To assemble some of these crusaders in one place seems only natural, and indeed, Vincent does so in the episode “Labyrinth,” a virtual dry run for “The Believers” that groups several Vincent converts around a UFO study at a small-town university.

Moreover, the Believers fit in with an effort on the part of the writers to make Vincent’s quest seem less hopeless by granting him the occasional victory. This trend began with the first season finale, “The Condemned,” in which eleven high-ranking aliens commit suicide after Vincent uncovers their secret identities, and continued into the second year. With the Believers backing him, Vincent manages to obtain film of two alien deaths (“Counterattack”), to gain possession of a part of a key alien weapon (“The Miracle”), and to add the resources of the world’s largest news-gathering organization to his fight (“Task Force”).

But for the producers, the addition of Scoville and company represented not a carefully thought-out way of adding more tension and credibility to The Invaders, but a desperate move to save the flagging series from cancellation.

“I think they really screwed it up even worse [when] they formed this committee,” said Anthony Spinner, who recalled discussing the addition of the Believers as early as the first season. “I remember Quinn was trying to tell me about it before I left, and I said, ‘Why is a committee any more interesting than one person?’ Which didn’t go down too well. I had my ups and downs with Quinn over fifteen years.”

According to Alan Armer, it was ABC, not Martin, who insisted on the change. “They found it difficult to believe that nobody wold go along with him, so I think it was [the nework’s] suggestion that there be a small coterie who worked with David Vincent . . . . But it took away from Roy somehow, and I went with it grudgingly because I felt somehow it took away from the kind of classic sense of one guy trying to [defeat a foe alone]. It may have seemed silly, but dammit, that’s what great storytelling is all about.”

With no one on the production staff enthusiastic about Vincent’s new allies, it’s no surprise that the twelve remaining episodes rarely recaptured the gritty, martial, almost hysterical feel of “The Believers.” Edgar Scoville took a backseat in most of these final adventures, sending Vincent back to business as usual as a solo alien-fighter. “The Organization” relies on some taut action scenes to carry off the uninspired idea of Vincent cooperating with the mafia to outwit some aliens. “Task Force” retells the familiar story of a weak-willed human (Linden Chiles, who had played Vincent’s brother in “Wall of Silence”) who sells out to the aliens.

The worst of the Believers episodes was probably “The Ransom,” in which Vincent holds an alien leader hostage in a mountain cabin occupied by a reclusive, ailing poet (Laurence Naismith). “Ransom,” yet another Fugitive rip-off, combines elements of two of that series’ 1967 episodes (“Run the Man Down” and “The Shattered Silence,” which cast Naismith in an identical role) and never seems to notice the irony of a conclusion that has the aliens saving Vincent’s life with their technology.

Roy Thinnes and Ahna Capri in “Counterattack”

On the other hand, a few episodes made intelligent enough use of the Believers concept to give Invaders fans a taste of what might have been. “Counterattack” shows the Believers mounting their first offensive against the aliens. The invaders respond not only by foiling their plans but by framing Vincent for murder – a seemingly inevitable scenario, in view of all the deaths that occur around him. Out on bail, a depressed Vincent turns to drink and even considers selling out to the aliens, while dissention rocks the ranks of the other Believers as they consider distancing themselves from the controversial Vincent. Unfortunately, writer Laurence Heath abandons this intriguing and (and overdue) conflict when he reveals Vincent’s supposed defection as part of an elaborate scheme to trick the invaders.

“The Life Seekers” offers a rare glimpse into the aliens’ background and politics, and profoundly changed the series’ concept of its antagonists. The episode introduces a pair of aliens (Barry Morse and Diana Muldaur) who oppose the invasion of Earth and, at the end of the episode, return to their home planet with evidence they hope will sway others of their kind. Muldaur’s character tells Vincent that the aliens already on Earth are the most vicious and brutal of their species, intimating that deceit on the part of this advance guard was partly responsible for convincing their leaders to proceed with the invasion. (Again, a Vietnam allegory is obvious.) She also reveals that the aliens have the equivalent of male and female sexes, and hints that some members of their species do feel emotion.

“The Pursued,” another intelligent outing, cast Suzanne Pleshette (in a variation on her “Mutation” role) as the product of an alien experiment in duplicating human emotions gone awry. Incredible Hulk-like, she goes homicidally berserk whenever something upsets her. The episode introduces some Believers who for once have a compelling backstory, and features the first child-alien (played by the future Greg Brady, Barry Williams: it would explain a lot if the entire Brady Bunch were in fact aliens in disguise). In a richly ironic finale, Vincent finally manages to get a living alien to Washington, but his shot at proving his claims is ruined at the last minute not by the aliens but by a man (Will Geer) who kills Pleshette to avenge the murder of his wife. “If only he hadn’t been so human,” Vincent says to Edgar Scoville.

Neither the arrival of the Believers nor the strong batch of year’s-end episodes came in time to save The Invaders. The show’s ratings had dropped consistently since its premiere, and by the end of the second season ABC was ready to give up. “We were doing fairly well, not brilliantly, but certainly by today’s standards it would have been a hit,” said Anthony Spinner. “But I think they were disappointed, ABC, because they spent so much money promoting it at the beginning. And that [when] they tested it, it had gone through the roof. They had huge expectations for it, so when it just did okay, there was a sense of disappointment.”

The last episode, “Inquisition,” cast Mark Richman as a McCarthy-like federal prosecutor who starts a witch-hunt to implicate the Believers in the assassination of a U.S. Senator. At the same time, Vincent and Scoville uncover evidence that the aliens have finally decided to stop fooling around and have built a sonic device that will wipe out all human life on Earth. During the race to stop them, Scoville is seriously wounded and still more Believers perish. Written by Barry Oringer, “Inquisition” has a few weak spots (there are, for example, only two aliens posted to guard the ultimate death machine) but on the whole it comes close to recapturing the urgency of “The Believers.”

It was a fine season finale, but a disappointing ending for the series. Unlike The Fugitive, The Invaders would not go out with the bang of a highly-rated final episode in which all the loose ends of the ongoing storylines were tied up. “I don’t know that we knew we were being cancelled when we did the last show,” said David Rintels.

Few at QM were sad to see the series depart. Alan Armer, who eventually left television production for a career in academia, felt that “it kind of became a downhill spiral. It just got sillier and sillier.” After the show wrapped, David Rintels turned down Quinn Martin’s offer to move over to the long-running The F.B.I. (Dubious about that show’s politics, Rintels had concealed his F.B.I. scripts behind the pseudonym Pat Riddle).

All along, Larry Cohen had monitored what he felt was the decline of his original concept. “As the show progressed and I tried to give them some advice on where I thought the show was going wrong, they weren’t interested,” recalled Cohen. “My advice was that there were too many invaders in every episode, that they were killing too many invaders and they were too easy to kill. So basically the invaders were no longer threatening, and they were no longer even interesting, because there were too many of them popping up everywhere and the fun of trying to guess who’s an invader and who isn’t was completely lost from the show. Everybody was an invader, and [David Vincent] was shooting them right and left and they were burning up right and left, and once you saw it there was nothing new about it and it became tiresome.”

Armer and Cohen criticize their creation too harshly. The Invaders may not have been cutting-edge science fiction, but it was a beautifully produced and vastly entertaining bit of escapism, a mood piece that still holds up thirty years later. It directly influenced Quinn Martin’s later entries into the genre (the shortlived 1977 anthology Tales of the Unexpected and a 1980 TV-movie called The Aliens Are Coming), as well as the most important sci-fi media event of the 1990s, the Fox network’s wildly popular series The X-Files. And The Invaders itself lives on, continually reinventing itself into the 21st century.